Table of Contents

- Saraswati at a Glance

- What Our Texts Say

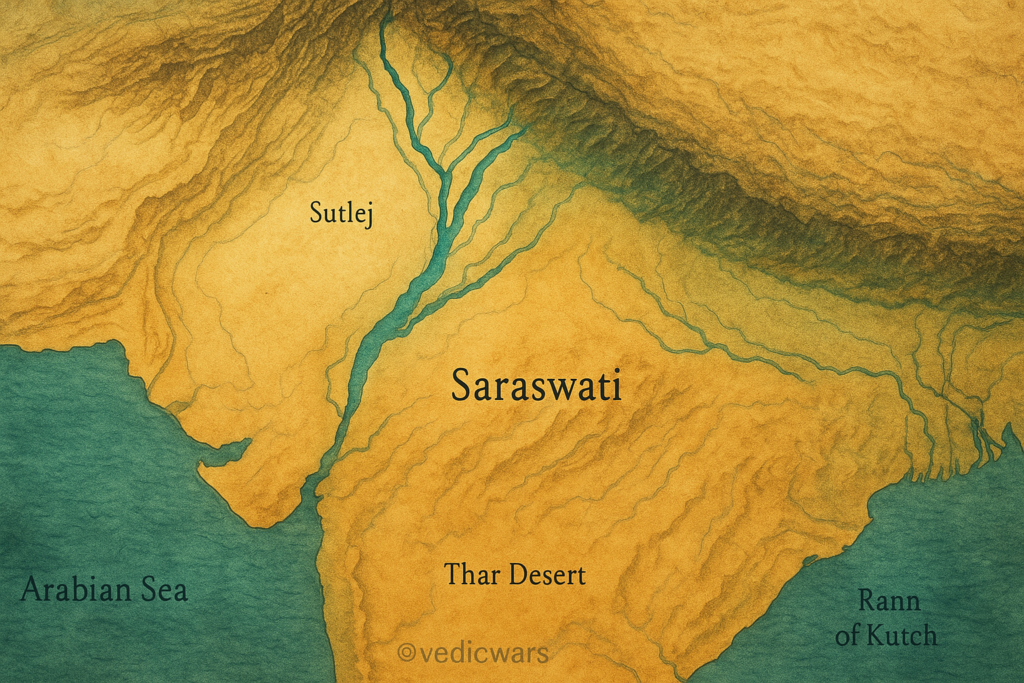

- Where Did Saraswati Flow?

- The Ghaggar–Hakra Identification

- River Capture: Yamuna & Sutlej

- Other Theories You’ll Hear

- What Science Finds

- Archaeology Along the Paleochannel

- Dating the Channels

- Satellite & Isotope Clues

- Myths vs. Facts

- A Simple Timeline

- Places You Can Visit Today

- Why the Saraswati Still Matters

- FAQs

- Image Pack: 5 SEO-Ready Visuals

- Author Note & How We Built This

- Sources

Saraswati at a Glance

- Who/What: The Lost River Saraswati is a sacred river praised in the Vedas and remembered across epics like the Mahabharata.

- Why “Lost”: Its visible flow diminished or shifted thousands of years ago; what remains are paleochannels—ancient river beds under today’s soil.

- Most Discussed Identification: The Ghaggar–Hakra system (India–Pakistan), with links to tributaries like the Sutlej and Yamuna in the distant past.

- Civilization Link: Hundreds of Harappan/Indus-Saraswati sites lie along these fossil channels, indicating dense settlement.

- Status Today: Parts are seasonal or dry; water appears in segments, canals, or at specific wells. The debate is how and when flows changed—not whether peoples lived there.

What Our Texts Say

The Rigveda often celebrates Saraswati as a mighty, nourishing river—“best of mothers, best of rivers,” a life-giver and purifier. In the Mahabharata, we find episodes set along or referencing Saraswati’s course, with hints that some sections were once perennial and later became seasonal.

Across Puranic literature, Saraswati acquires cosmic and symbolic meaning—flowing not just across the land but through learning, speech, and wisdom. This dual identity—physical river and spiritual force—is why the debate is passionate. For believers, she is ever-present. For historians, she is a river system whose story is told in sediments, settlements, and shifting channels.

What Science Finds

Archaeology Along the Paleochannel

Archaeologists have mapped site density along Ghaggar–Hakra paleochannels, including major and minor settlements. Well-known sites include Rakhigarhi (Haryana), Kalibangan (Rajasthan), Bhirrana, Banawali, Dholavira (Gujarat; connected via the broader regional network), and numerous smaller habitations and craft localities.

Patterns show:

- Urban and rural sites aligned with ancient watercourses.

- Craft specializations (beads, ceramics, copper/bronze items) that required reliable water for production and trade.

- Phased change—over centuries, some places declined, others adapted, suggesting water stress or channel changes.

Dating the Channels

Two methods frequently used in this region:

- Radiocarbon dating of organic remains from settlements or channel deposits.

- Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating of sands to figure out when sediments last saw sunlight (i.e., were deposited by flowing water).

Broad takeaways used by scholars:

- Significant flows likely existed during the early to mature Harappan phases.

- Later, flows attenuated, shifted, or became irregular, aligning with broader climate variability across the subcontinent.

Important: Scientists differ on exact timelines and intensity of flow. The consensus trend is that rivers and climates change, and the Ghaggar–Hakra corridor clearly supported large populations in antiquity.

Satellite & Isotope Clues

- Satellite imagery (multispectral/thermal) helps trace buried channels beneath farms and desert.

- Isotopic signatures in groundwater or sediments can show if water once came from glacier-fed sources (like Sutlej/Yamuna) or rain-fed local streams.

- The emerging picture is complex but consistent with: (a) long-lived channels; (b) tributary changes; (c) human adaptation.

Myths vs. Facts

Myth 1: “If the river isn’t flowing today, it never existed.”

Fact: Ancient rivers can migrate, vanish on the surface, or survive as subsurface aquifers. Paleochannels are real, mappable features.

Myth 2: “Saraswati must be a single, straight, unchanging line.”

Fact: Rivers are dynamic. Over millennia they split, braid, and rejoin. Multiple segments can carry the same sacred name in literature.

Myth 3: “Either the Ghaggar–Hakra is Saraswati or the theory fails.”

Fact: Identifications can be regional or multi-phase. A “Saraswati system” could include tributaries that fed different branches at different times.

Myth 4: “If it was perennial once, it must be perennial forever.”

Fact: Monsoon shifts, tectonics, and river capture can reduce or move flows dramatically over time.

Myth 5: “Archaeological sites prove a single narrative.”

Fact: Sites prove dense human presence and water use. The cause-and-effect (which river, which century, which flow strength) is a scientific debate still being refined.

A Simple Timeline

- Pre-Harappan/Early Harappan (c. 5000–2600 BCE): Populations cluster along favorable channels; agriculture expands; early craft production rises.

- Mature Harappan (c. 2600–1900 BCE): Urban networks flourish; Ghaggar–Hakra corridor shows high site density. Water is abundant through rivers, groundwater, tanks, and seasonal streams.

- Late Harappan/Transition (c. 1900–1300 BCE): Site shifts, ruralization in some areas; flow reductions or channel changes likely.

- Iron Age/Epic Period (later): Cultural memory preserves Saraswati as sacred; parts of the channel turn seasonal or subterranean.

- Medieval to Modern: Canals, wells, and local streams support farming; paleochannels remain detectable via imagery and field surveys.

Places You Can Visit Today

Travel respectfully. Check current site status, permissions, and local museum hours.

- Rakhigarhi (Haryana): One of the largest Harappan sites. Museum development has improved public understanding; expect evolving infrastructure.

- Kalibangan (Rajasthan): Town planning, fire altars, and ceramic remains highlight ritual and daily life.

- Bhirrana (Haryana): Early layers indicating long settlement history.

- Banawali (Haryana): Fortified settlement plan typical of the region.

- Dholavira (Gujarat): Farther southwest but crucial for understanding water engineering—reservoirs, step-wells, and urban design that show how the wider civilization managed water.

Tip: Also explore regional museums and local universities for maps of paleochannels and exhibit guides; they often have models that make the river story visible.

Why the Saraswati Still Matters

- Cultural Memory: Saraswati connects learning, speech, and purity. She’s invoked in education and arts even today.

- Historical Clarity: Understanding her course clarifies settlement patterns, trade routes, and environmental change in the subcontinent.

- Water Policy: Ancient solutions—tanks, step-wells, canalization, flood management—hold lessons for modern water stress.

- Identity & Dialogue: A people-first approach helps us appreciate beliefs and science together—not to “win,” but to learn.

FAQs

Q1. Is the Lost River Saraswati the same as the Ghaggar–Hakra?

A. Many scholars correlate them, especially for certain periods. The identification is strongest at a regional and time-bound scale, not as a single, unchanging river.

Q2. Did the Saraswati flow from the Himalaya to the sea?

A. Evidence suggests strong flows in the past with tributary contributions and downstream dispersal toward the Rann of Kutch region. Exact routing changed through time.

Q3. Why did it “vanish”?

A. Likely a combination of river capture (Sutlej/Yamuna path changes), monsoon variability, tectonics, and sediment dynamics.

Q4. Is there water under the old bed today?

A. Yes, in places. Groundwater tied to ancient channels is a key reason why agriculture remains possible across parts of the corridor.

Q5. Is this debate political?

A. The science is geological and archaeological. Interpretations vary, but the core methods—mapping, dating, sediment study—are standard across the world.

Q6. Can I see the river itself today?

A. You can see segments, canals, and seasonal flows, especially after rains. The paleochannel is best “seen” via maps, museum exhibits, and on the landscape as subtle levees and alignments.

Author Note & How We Built This

This article follows people-first guidelines: clear definitions, balanced views, and practical takeaways. It reflects on-ground archaeology, geology methods (OSL/radiocarbon), and remote sensing—explained in simple language so you can judge claims for yourself. No external links are included per site policy. If you want, we can add citations later.

If you found this useful, explore our related stories on Harappan water engineering, Rakhigarhi discoveries, and myths vs history in Indian epics. Comment below: What part of the Saraswati story fascinates you most—the science, the scriptures, or the living culture?

Sources

- Rigveda hymns to Saraswati (standard translations)

- The Sarasvati River in the Rigveda – scholarly overviews

- Archaeological Survey reports on Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, Bhirrana, Banawali, Dholavira

- Geological papers on Ghaggar–Hakra paleochannels, OSL dating, and river capture involving Sutlej and Yamuna

- Museum catalogues and regional surveys from Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat