Introduction: The Vast Tapestry of the Mahabharata War

The Mahabharata War remains the quintessential conflict of Indian antiquity, a cataclysmic event that signaled the end of the Dvapara Yuga and the dawn of the Kali Yuga. When the collective imagination turns to this eighteen-day Armageddon, it invariably focuses on the titans of the epic: the peerless archer Arjuna, the tragic solar hero Karna, the grandsire Bhishma, and the divine strategist Krishna. These figures dominate the narrative landscape, their rivalries, vows, and philosophical dilemmas forming the central pillars of the saga. However, the Mahabharata War is not merely the story of five brothers against one hundred cousins. It is a sprawling, interconnected web of karma involving millions of warriors, celestial beings, tribal kings, and sorcerers, each playing a critical, mechanical role in the engine of destiny.

To fully comprehend the magnitude of the Mahabharata War, one must look beyond the center stage. One must gaze into the shadows where the “Unsung Heroes” operated. These are the warriors who, through acts of supreme sacrifice, terrifying magical prowess, or unwavering adherence to their specific interpretation of Dharma, influenced the outcome of the war just as significantly as the great Maharathis. Some were destined to die before the first arrow flew to sanctify the battlefield; others were cursed to fight against their own conscience, bound by ancient oaths or trickery. Some, like Barbarika and Iravan, are worshipped today as supreme deities in specific regions of India, despite their stories being relegated to the margins of standard retellings.

This report serves as a definitive deep dive into these lesser-known warriors. We will explore the tragedy of the Naga prince Iravan, the cosmic power of the demon Barbarika, the moral courage of Vikarna, and the complex loyalties of Shalya and Yuyutsu. By analyzing their lineages, their specific battles, and their psychological burdens, we uncover a fresh perspective on the Mahabharata War—one that reveals that history is often written by the survivors, but it is built on the bones of the unsung.

Table of Contents

- The Sacrificial Sons: Magic and Destiny

- Barbarika: The Three-Arrow Observer

- Ghatotkacha: The Pot-Headed Destroyer

- Iravan: The Naga Prince and the Groom of Death

- The Voices of Conscience: Dharma in the Court of Sin

- Vikarna: The Sole Defender of Draupadi

- Yuyutsu: The Brother Who Crossed Over

- The Yadava Warlords: Krishna’s Muscle

- Satyaki: The Tiger of the Vrishnis

- Kritavarma: The Conspirator in the Shadows

- The Tragic Veterans: Honor Bound by Old Oaths

- Bhurishravas: The Hero Denied a Warrior’s Death

- Bhagadatta: The Thunder on Supratika

- Shalya: The Poisoned Charioteer

- Modern Legacy and Iconography

- FAQ Section

- Conclusion

1. The Sacrificial Sons: Magic and Destiny

The Mahabharata War was not fought solely with steel, chariots, and orthodox archery; it was also a war of Maya (illusion), sorcery, and celestial lineages. The Pandava bloodline, specifically through the mighty Bhima and the dexterous Arjuna, produced sons born of non-human mothers—Rakshasis and Naginis. These hybrid warriors possessed powers that defied the conventions of Aryan warfare, making them pivotal, yet tragic, assets who were often expended by the divine strategist Krishna to protect the core Pandava brothers.

Barbarika: The Three-Arrow Observer

Perhaps the most potent “what if” in the entire Mahabharata War is the story of Barbarika (often worshipped as Khatu Shyam). He is a figure of immense fascination because his power was absolute, yet he never fired a single shot in the actual eighteen-day conflict. His story serves as a metaphysical boundary for the war; had he participated, the war would have ceased to be a contest of valor and become a momentary extermination.

Lineage and Power Barbarika was the son of Ghatotkacha and the princess Maurvi (also known as Ahilawati). This lineage makes him the grandson of Bhima and the demoness Hidimbi. From his mother, a woman of great martial prowess and daughter of the demon Mura, Barbarika learned the tactics of warfare. However, his true power was not merely genetic.

Through severe penance to Lord Shiva and Agni, he acquired the Teen Baan (Three Infallible Arrows) and a divine bow. These weapons elevated him beyond the status of a Maharathi to a cosmic force capable of rewriting destiny.

The Theory of the Three Arrows Barbarika is often cited as the most efficient warrior in the mythology surrounding the epic. While Bhishma, Drona, and Karna estimated they would need weeks to annihilate the opposing armies, Barbarika claimed he could end the Mahabharata War in one minute. The mechanism of his arrows was unique, functioning on a logic of selection rather than kinetic impact.

| Arrow Sequence | Function | Mechanism of Action |

| First Arrow | Target Identification (Destruction) | Marks all targets the archer wishes to destroy. It uses a red powder (vermilion) to tag the specific entities. |

| Second Arrow | Target Identification (Protection) | Marks all targets the archer wishes to protect/save. |

| Third Arrow | Execution | Destroys everything marked by the first arrow (or unmarked by the second) and returns to the quiver. |

This binary logic meant Barbarika required no armies, no supply lines, and no strategy. He simply needed to identify the targets. However, this power came with a binding vow of chivalry: he had promised his mother he would always fight for the “weaker side” (Haare Ka Sahara).

Krishna’s Test and the Leaf Paradox The legend, primarily found in the Skanda Purana (Kaumarika Khanda) rather than the critical edition of the Mahabharata, details a meeting between a disguised Krishna and Barbarika en route to Kurukshetra. Krishna mocked the warrior for carrying only three arrows to a war involving millions. To test him, Krishna asked Barbarika to pierce every leaf on a nearby Peepal tree.

Barbarika released his first arrow to mark the leaves. While the arrow was in flight, Krishna stepped on a fallen leaf, hiding it under his foot. The arrow, having marked all the visible leaves on the tree, began to hover menacingly over Krishna’s foot. Barbarika, recognizing the nature of his weapon, warned the Brahmin (Krishna), “Lift your foot, or the arrow will pierce it to find the hidden leaf”.

This incident confirmed Barbarika’s omnipotence to Krishna, but it also highlighted the catastrophic implication of his vow to support the losing side.

- Scenario A: If Barbarika joined the Pandavas (initially the weaker side numerically), he would decimate the Kauravas.

- Scenario B: Once the Kauravas were reduced to a minority, they would become the weaker side.

- Scenario C: Barbarika would be forced by his vow to switch sides and fight the Pandavas.

- The Infinite Loop: He would oscillate back and forth like a pendulum, obliterating whichever side was losing until only he remained alive.

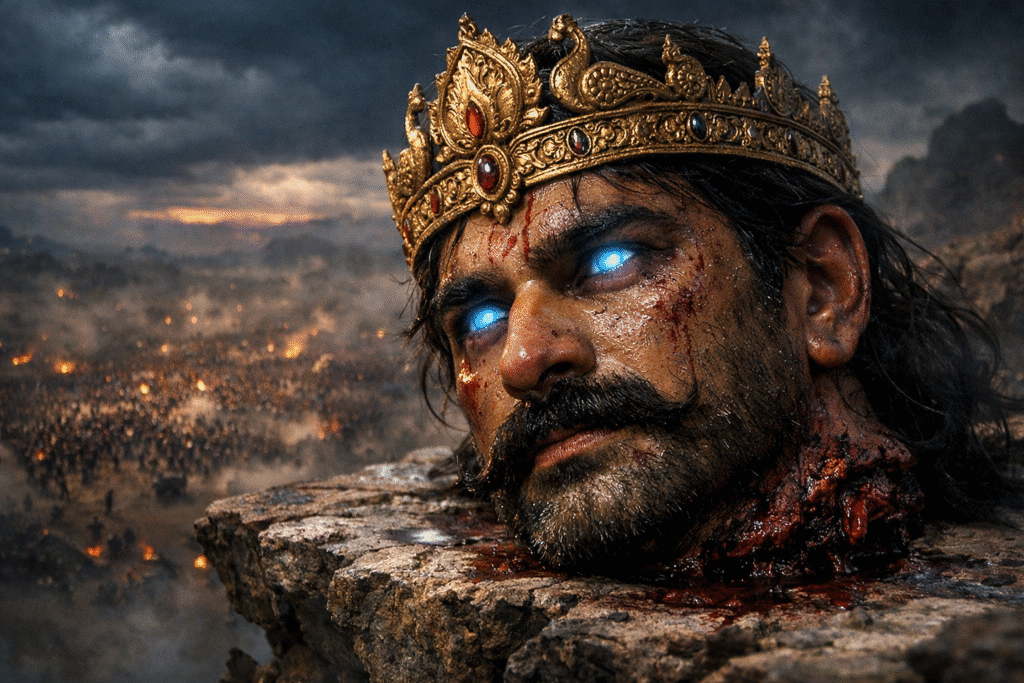

The Ultimate Sacrifice To prevent this mutual annihilation and ensure the survival of Dharma (represented by the Pandavas), Krishna asked for charity (daan) from the warrior. Barbarika agreed, and Krishna demanded his head. Barbarika, realizing the Brahmin was Krishna, surrendered but asked for a boon: to witness the Mahabharata War.

Krishna granted this. Barbarika cut off his own head, which was placed on a hill overlooking Kurukshetra. From this vantage point, he became the silent witness to the carnage. When asked later by the victorious Pandavas who was truly responsible for the victory, the head of Barbarika replied that he saw only two things: Krishna’s Sudarshana Chakra destroying evil and Draupadi as Mahakali drinking the blood of sinners. This revelation humbled the Pandavas, stripping them of their ego and highlighting that they were merely instruments in a divine play.

Ghatotkacha: The Pot-Headed Destroyer

While Barbarika is a legend of the Puranas, his father Ghatotkacha is a central figure in the canonical Mahabharata text (Drona Parva). He was the son of Bhima and the Rakshasi Hidimbi. His name, “Ghatotkacha,” is derived from the shape of his head, which resembled a pot (Ghata) and was hairless (Utkacha).

The Rakshasa Nature and Iconography Ghatotkacha represents the terrifying integration of non-Aryan magic into the Mahabharata War. As a half-Rakshasa, he possessed immense physical strength, the ability to change size, fly, and cast Maya (illusions).

Descriptions in the text paint him as a “gigantic” figure with blood-red eyes, a copper hue, and a body covered in bristles. He wore a brass cuirass and wielded a massive bow, his chariot adorned with bear skins and blood-red banners. Crucially, Rakshasa powers wax and wane with the solar cycle; they are weakest at day and invincible at night.

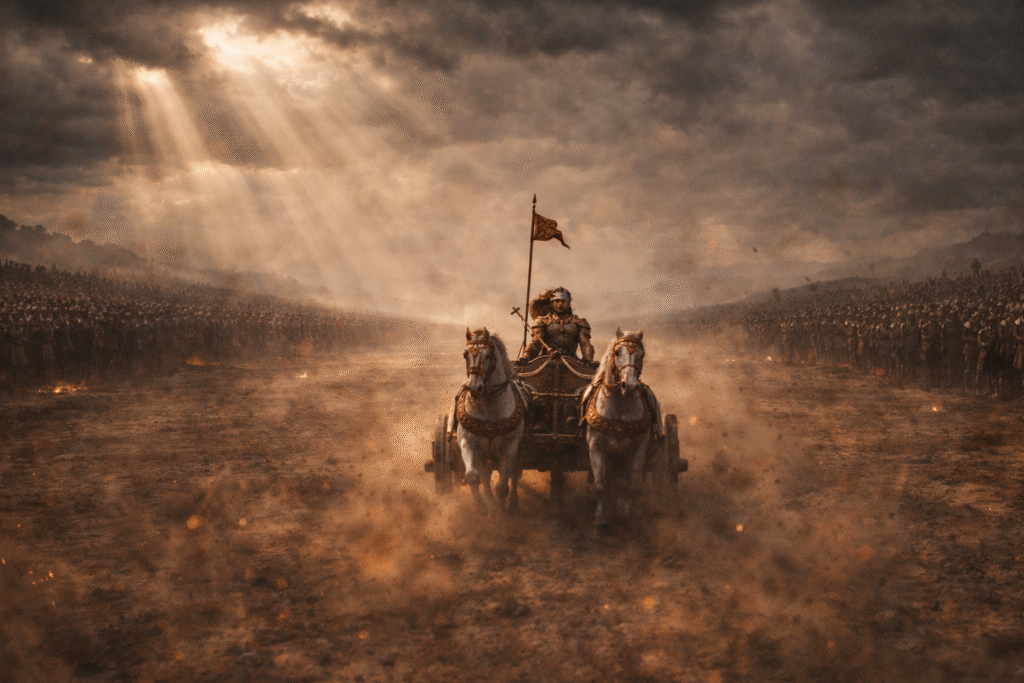

The Night War (Drona Parva) The turning point for Ghatotkacha—and the war itself—occurred during the night battle of the 14th day (continuing into the 15th). Warfare rules generally prohibited fighting after sunset, but passions were so high after Jayadratha’s death that the armies continued clashing under the moonlight.

This environment favored Ghatotkacha perfectly. He unleashed havoc on the Kaurava army, using celestial weapons and demonic sorcery. He summoned an army of illusions, raining meteors, iron wheels, and stones upon the Kauravas. He fought the Rakshasa Alambusha (who had killed his cousin Iravan) and defeated him, tearing him apart. The Kaurava army, unable to cope with the supernatural assault, began to flee in terror.

The Exchange: Ghatotkacha for Arjuna Duryodhana, terrified by the Rakshasa’s rampage, begged Karna to intervene. Karna possessed the Vasavi Shakti (also known as the Amogha Shakti or Indra’s Dart). This weapon was infallible but could be used only once before returning to the heavens. Karna had been saving this specific weapon for years with the sole intention of killing Arjuna.

Krishna, the master strategist, knew this. He encouraged Ghatotkacha to press the attack on Karna. Ghatotkacha fought valiantly, using illusions to bewilder the solar warrior—disappearing, reappearing, and creating multiple copies of himself. Pushed to the brink and seeing the Kaurava army facing annihilation, Karna was forced to hurl the Vasavi Shakti at Ghatotkacha. The Rakshasa was pierced and killed, but in his final moments, he performed one last act of service for the Pandavas. He enlarged his body to a colossal size and fell upon the Kaurava army, crushing thousands of soldiers and elephants in death.

The Aftermath and Insight While the Pandavas grieved the loss of their nephew, Krishna danced with joy. He revealed to a shocked Arjuna that Ghatotkacha’s death had saved Arjuna’s life. By forcing Karna to expend the Shakti, the greatest threat to the Pandava victory was removed. Ghatotkacha is the ultimate unsung hero because he was literally “fed” to the enemy’s strongest weapon to protect the “chosen one.” His sacrifice was not accidental; it was a calculated tactical exchange orchestrated by Krishna.

Iravan: The Naga Prince and the Groom of Death

Iravan (also known as Aravan) is another son of the Pandavas who met a tragic, sacrificial end. He was the son of Arjuna and the Naga princess Ulupi. Raised in the serpent kingdom, he joined his father on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, bringing with him a battalion of Naga warriors.

The Perfect Sacrifice In the Mahabharata text (Bhishma Parva), Iravan fights valiantly, killing five brothers of Shakuni before being slain by the Rakshasa Alambusha. However, the South Indian tradition (specifically the Koovagam cult and Draupadi Amman cult) offers a much deeper, more complex mythology that elevates Iravan from a minor warrior to a primary deity.

According to this tradition, the Pandavas needed to perform a Kalappali—a sacrifice of a perfect male with 32 auspicious marks—to Goddess Kali to ensure victory before the war began. Only three people qualified: Krishna, Arjuna, and Iravan. Since Krishna and Arjuna were indispensable leaders, Iravan volunteered to be the sacrificial offering.

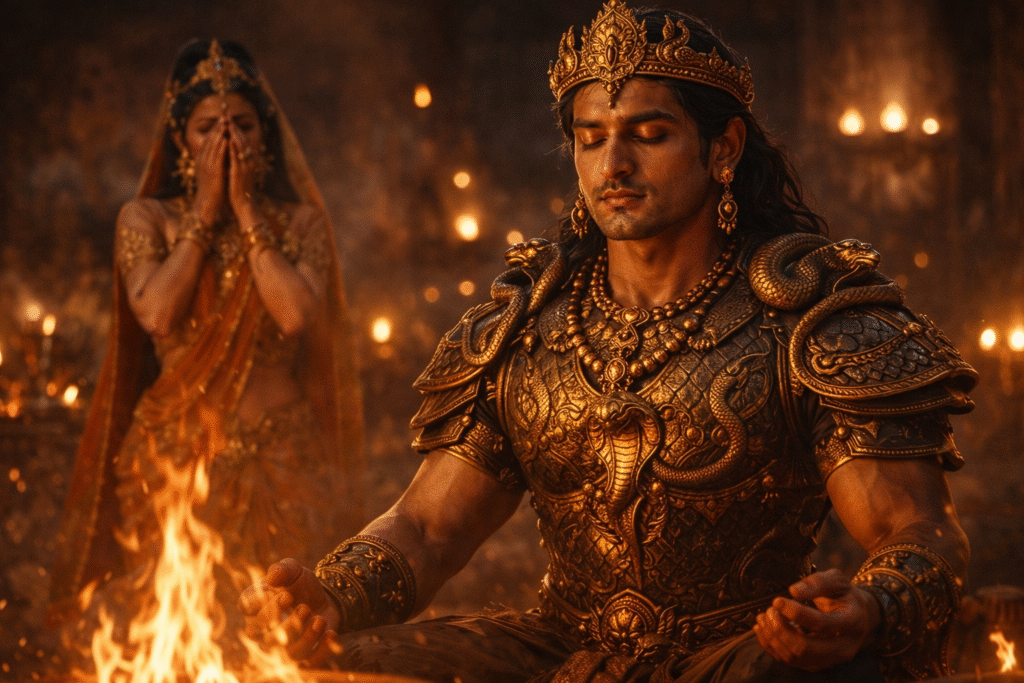

The Last Wish and the Wedding of Mohini Before being beheaded, Iravan had a final request: he wished to die married. He did not want to leave the world a bachelor, nor did he want to die without experiencing the joys of union. However, no king was willing to give his daughter to a man destined to die the next morning.

To fulfill this wish, Lord Krishna transformed himself into the enchantress Mohini. Mohini married Iravan, and they spent the night together in marital bliss. The next morning, after Iravan was sacrificed, Mohini (Krishna) wept as a widow, breaking her bangles, beating her chest, and mourning her husband like any grieving wife.

Modern Legacy: The Koovagam Festival This myth is the foundation of the annual festival at Koovagam, Tamil Nadu. The Aravanis (transgender community/Hijras) identify with Mohini. Each year, thousands of transgender women “marry” Lord Aravan in the temple. The priests tie the thali (wedding thread) around their necks. The next day, when the idol of Aravan is symbolically beheaded, they mourn as widows, re-enacting Krishna’s grief by cutting the thali and breaking their bangles. This transforms Iravan from a minor war casualty into a powerful symbol of gender fluidity and divine acceptance.

2. The Voices of Conscience: Dharma in the Court of Sin

While the war was fought with weapons, the seeds were sown in the royal court of Hastinapura. Among the Kauravas, who are typically painted as a monolith of evil led by Duryodhana, two brothers stood out for their adherence to Dharma. Their stories highlight the internal conflict of the Kuru clan.

Vikarna: The Sole Defender of Draupadi

Vikarna was one of the hundred sons of Dhritarashtra and Gandhari. He is often called the “Kumbhakarna of the Mahabharata”—a righteous man fighting on the wrong side. His defining moment occurred not on the battlefield, but in the assembly hall.

The Dyuta Sabha Incident During the shameful game of dice (Dyuta Sabha), when Draupadi was dragged into the assembly and disrobed, the entire court—including the wise Bhishma, Drona, and Kripa—sat in stunned, impotent silence. Vikarna was the only Kaurava to stand up and protest. He raised a legal and moral objection that cut through the silence:

- Legal Argument: Yudhishthira had already gambled himself into slavery. A slave has no property rights; therefore, he had no right to stake Draupadi.

- Moral Argument: He condemned the silence of the elders, demanding they answer Draupadi’s question.

His speech was fiery and direct: “Ye kings, answer the question that hath been asked by Yajnaseni!… regarding this matter, I do not think that she hath been won in accordance with the ordinance”. This act of defiance enraged Karna, who ridiculed him, calling him a child who spoke out of turn. Karna then ordered Duhshasana to continue the disrobing, silencing Vikarna’s lone voice of reason. The Tragic End Despite his righteousness, Vikarna remained loyal to his brother Duryodhana during the war. He believed his duty as a brother (Bhratra Dharma) outweighed the larger morality of the conflict.

On the battlefield, he eventually faced Bhima. Bhima, who had sworn to kill all one hundred Kaurava brothers, hesitated when he saw Vikarna. He remembered Vikarna’s defense of Draupadi and offered to spare him. Vikarna refused, stating that he could not abandon his brother in war. Bhima killed him with a heavy heart, later lamenting that Vikarna was a “man of Dharma” who deserved better. Vikarna’s story highlights the nuance of the epic: one can be a good man but still be trapped by bad loyalty.

Yuyutsu: The Brother Who Crossed Over

Yuyutsu provides a foil to Vikarna. He was the son of Dhritarashtra, but born of a maid (Sughada), making him a half-brother to the Kauravas. Because of his maternal lineage, he was often sidelined, yet he possessed a clarity of conscience that his high-born brothers lacked.

The Choice Just before the Mahabharata War began, Yudhishthira stood before the armies and made an open proclamation: “He who wishes to join us, let him come over now; he who wishes to leave us, let him go.” Amidst the silence of the Kaurava ranks, only Yuyutsu moved. Disgusted by the actions of his half-brothers and recognizing the righteousness of the Pandava cause, he drove his chariot out of the Kaurava formation and joined the Pandavas to the beat of drums.

The Survivor This decision saved his life. Yuyutsu became the only son of Dhritarashtra to survive the war. He fought valiantly for the Pandavas, often engaging in fratricidal combat against his half-brothers. After the war, his role became crucial.

When the Pandavas renounced the throne to climb the Himalayas, it was Yuyutsu who was entrusted with the regency of Hastinapura. He served as the guardian for the young King Parikshit (Arjuna’s grandson). Yuyutsu represents the difficult path of placing morality above family—a choice Vikarna could not make. His survival suggests that Dharma protects those who protect it.

3. The Yadava Warlords: Krishna’s Muscle

The Yadavas were the people of Krishna, but they were divided in the Mahabharata War. Due to a promise made by Krishna to both Arjuna and Duryodhana, his personal army (the Narayani Sena) fought for Duryodhana, while Krishna himself (as a non-combatant charioteer) joined Arjuna. This split the Yadava commanders, pitting kinsman against kinsman in a civil war within the great war.

Satyaki: The Tiger of the Vrishnis

Satyaki (also known as Yuyudhana) was Krishna’s cousin and Arjuna’s student. He is described as a warrior of equal prowess to the great Maharathis. Unlike the rest of the Yadava army, Satyaki refused to fight for the Kauravas. His devotion to Krishna and his friendship with Arjuna were paramount, leading him to bring a small Akshauhini of Vrishni troops to the Pandava side.

The Savior of the 14th Day Satyaki’s finest hour came during the desperate race to kill Jayadratha on the 14th day. With Arjuna deep inside the Chakra-vyuha, Yudhishthira sent Satyaki to support him. Satyaki smashed through the Kaurava lines, defeating Drona (by bypassing him with a clever maneuver), killing Jalasandha, and holding off waves of attacks. He acted as the shield that protected Yudhishthira from capture while simultaneously cutting a path to Arjuna.

The Rivalry with Bhurishravas Satyaki’s story is intertwined with a multi-generational blood feud involving the Kuru commander Bhurishravas. Years prior, Satyaki’s grandfather (Sini) had defeated Bhurishravas’s father (Somadatta) in a bridal contest. This humiliation festered into a hatred that exploded on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, leading to one of the most controversial duels of the war (discussed in the next section).

Kritavarma: The Conspirator in the Shadows

Kritavarma was the commander of the Narayani Sena—the Yadava army gifted to Duryodhana. He is a darker, more pragmatic character compared to the idealistic Satyaki.

The Syamantaka Jewel Feud The tension between Satyaki and Kritavarma wasn’t just political; it was personal. Kritavarma had been complicit in a plot to steal the legendary Syamantaka jewel and murder Satrajit (Satyabhama’s father). Satyaki, being a relative of Satyabhama, held a deep grudge against Kritavarma for this betrayal. This backstory adds a layer of bitter internal conflict to the Yadava participation in the war.

The Massacre at Night (Sauptika Parva) Kritavarma is one of the three survivors of the Kaurava side (along with Ashwatthama and Kripacharya). His role in the end was horrific. He guarded the gates of the Pandava camp while Ashwatthama went inside and slaughtered the sleeping Upapandavas (sons of Draupadi) and the Panchala army. Kritavarma did not kill the sleepers himself, but he cut down anyone trying to escape the slaughter, ensuring no survivors. This complicity in the “night raid” marked him as a warrior who had abandoned the codes of Kshatriya Dharma.

The End of the Yadavas Years after the war, the animosity between Satyaki and Kritavarma caused the destruction of the entire Yadava race. During a drunken revelry at Prabhasa, Satyaki insulted Kritavarma for killing sleeping warriors (a cowardly act). Kritavarma retorted by bringing up Satyaki’s killing of the unarmed Bhurishravas. The argument turned into a brawl; Satyaki beheaded Kritavarma, and in the ensuing chaos, the Yadavas killed one another with grass reeds that turned into iron rods (Mausala Parva).

4. The Tragic Veterans: Honor Bound by Old Oaths

The Mahabharata War featured several veteran warriors who were not Kauravas by blood but were bound to them by alliances, trickery, or ancient enmities against the Pandavas.

Bhurishravas: The Hero Denied a Warrior’s Death

Bhurishravas was a prince of the Bahlika kingdom and a mighty Maharathi. He is often considered one of the most underrated fighters in the epic.

The Duel with Satyaki On the 14th day, Bhurishravas intercepted an exhausted Satyaki. The two engaged in a fierce duel. Bhurishravas, being fresh and skilled, gained the upper hand. He knocked Satyaki down, dragged him by the hair, and prepared to cut off his head with his sword.

The Intervention of Arjuna Krishna alerted Arjuna to Satyaki’s peril. Arjuna, from a distance, fired an arrow that severed Bhurishravas’s arm (the one holding the sword). Bhurishravas, in shock, turned to Arjuna and rebuked him for interfering in a personal duel, calling it an act of cowardice (Adharma). Arjuna defended his action, stating that Satyaki was his ally and was defenseless.

The Praya Realizing his time had come, Bhurishravas sat down on the battlefield, spread kusa grass, and entered a state of meditation (Praya), intending to fast unto death. While he was in this holy state, Satyaki regained consciousness, picked up his sword, and swiftly decapitated the meditating Bhurishravas. The entire battlefield condemned Satyaki for this act, but Satyaki justified it as fulfillment of his vow to kill him. This incident is a key case study in the degradation of Dharma as the war progressed.

Bhagadatta: The Thunder on Supratika

Bhagadatta was the King of Pragjyotisha (modern-day Assam) and the son of the demon Narakasura. He was an elderly warrior, described as having wrinkles that hung over his eyes (which he tied back with a silk cloth to see).

Supratika the Elephant Bhagadatta rode a colossal elephant named Supratika. This beast was a descendant of the celestial elephants (Diggajas) and was a weapon of mass destruction. In the battle, Supratika crushed chariots and terrified the Pandava army. There is a famous artistic depiction of Bhima being trampled by Supratika, only to survive by hiding under the elephant’s belly and attacking it from below.

The Vaishnavastra During his duel with Arjuna, Bhagadatta invoked the Vaishnavastra—a weapon of Lord Vishnu given to his father Narakasura. It was irresistible. Krishna, recognizing the weapon, stood up in the chariot and took the hit himself. The weapon turned into a floral garland around Krishna’s neck. Krishna explained that the weapon belonged to him (as Vishnu) and thus returned to its source. With the divine weapon neutralized, Arjuna was able to kill Bhagadatta by piercing the silk cloth binding his eyelids, blinding him, and then shooting him in the heart.

Shalya: The Poisoned Charioteer

Shalya was the King of Madra and the brother of Madri (Pandu’s second wife). He was the maternal uncle of Nakula and Sahadeva. He effectively loved the Pandavas but fought for the Kauravas due to a trick.

The Hospitality Trap On his way to join the Pandavas with a massive army, Shalya was treated to a lavish feast at every rest stop. Thinking Yudhishthira had arranged it, he offered a boon to the host. Duryodhana stepped out and revealed he was the host. Bound by his word, Shalya was forced to pledge his army to the Kauravas.

The Psychological Warfare Yudhishthira, realizing the loss, asked a secret favor of his uncle: “Fight for them, but when you drive Karna’s chariot, demoralize him.” Shalya fulfilled this promise. In the Karna Parva, as he drove Karna into battle against Arjuna, Shalya constantly insulted Karna, praising Arjuna’s superior skill, calling Karna a “low-born son of a Suta,” and predicting his death. This psychological warfare chipped away at Karna’s confidence at the crucial moment, distracting him when he needed focus the most.

The Final Commander After Karna’s death, Shalya became the Commander-in-Chief on the 18th day. He fought with surprising vigor but was eventually killed by Yudhishthira in a spear duel—a rare moment of martial prowess for the eldest Pandava.

5. Modern Legacy and Iconography

The fascinating aspect of these “Unsung Heroes” is that while they are secondary in the text, they are primary in worship. Their cults have outlived the kingdoms they fought for.

The Cult of Khatu Shyam

Barbarika is worshipped as Khatu Shyam in Rajasthan and Haryana. The legend says Krishna was so pleased with his sacrifice that he granted Barbarika his own name (“Shyam”). The temple in Sikar attracts millions of devotees. He is depicted as a severed head with a mustache, often adorned with flowers and a crown. Devotees believe he grants wishes to the “hopeless,” staying true to his vow of helping the weak.

The Cult of Koovagam

Iravan is the central deity of the Koovagam festival. His sacrifice is not seen as a tragedy but as a divine marriage. The visual description of Iravan in idols often shows him with a red face and large, fierce eyes (representing his moment of death) or as a severed head protected by a cobra hood (referencing his Naga lineage). This festival is a vital cultural space for the transgender community in India.

The Shadow Puppets of Java

In Indonesia, Ghatotkacha (Gatotkaca) is a superhero. In Wayang Kulit (shadow puppetry), he is a flying knight (Satria), depicted with a fierce face but noble bearing. He is the symbol of loyalty and aerial defense. Unlike the Indian version where he is a Rakshasa, the Javanese version emphasizes his warrior nobility.

6. FAQ Section

Q1: Was Barbarika mentioned in the original Mahabharata War text by Vyasa? A: No, Barbarika (or the story of the three arrows) does not appear in the critical edition of Vyasa’s Mahabharata. His story is primarily found in the Skanda Purana and later regional folklore. However, he has become an integral part of the Mahabharata tradition in North India.

Q2: Why did Yuyutsu side with the Pandavas in the Mahabharata War? A: Yuyutsu chose the Pandavas because he prioritized Dharma (righteousness) over family loyalty. He was disgusted by Duryodhana’s actions, particularly the disrobing of Draupadi and the refusal to grant the Pandavas their land. He was the only son of Dhritarashtra to survive the war.

Q3: How did Krishna save Arjuna from the Vaishnavastra? A: When Bhagadatta fired the Vaishnavastra (a weapon of Lord Vishnu) at Arjuna, Krishna stood up and received the weapon on his chest. Since Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu, the weapon recognized its master and turned into a garland of flowers, saving Arjuna from certain death. Q4: Who was the last commander of the Kaurava army?A: After the deaths of Bhishma, Drona, and Karna, Shalya was appointed as the Commander-in-Chief on the 18th day. After Shalya’s death, Ashwatthama briefly took command for the night raid.

7. Conclusion: The Architecture of Destiny

The Mahabharata War is often reduced to a binary conflict of Dharma vs. Adharma, personified by the Pandavas and Kauravas. However, a closer examination of these unsung heroes reveals a greyer, more intricate reality.

The war was won because a demon prince (Ghatotkacha) absorbed a divine weapon intended for Arjuna. It was won because a Naga prince (Iravan) offered his blood to Kali before the first arrow flew. It was won because a righteous brother (Yuyutsu) had the courage to defect, and a trapped uncle (Shalya) had the guile to poison the enemy’s mind. It was watched by the severed head of a grandson (Barbarika) who saw the truth that eluded the combatants: that the war was merely a play of the divine.

These characters, lurking in the shadows of the epic, remind us that in the grand design of fate, there are no small parts. Every boon, every curse, and every drop of blood contributed to the final outcome. To forget them is to read only half the story.

Did this deep dive change your perspective on the Mahabharata War? Which unsung hero resonates most with you—the sacrificial Iravan or the omnipotent Barbarika? Share your thoughts in the comments below, or explore our related article: “Sacred Ecology: Timeless Myths for a Greener Life“