Introduction

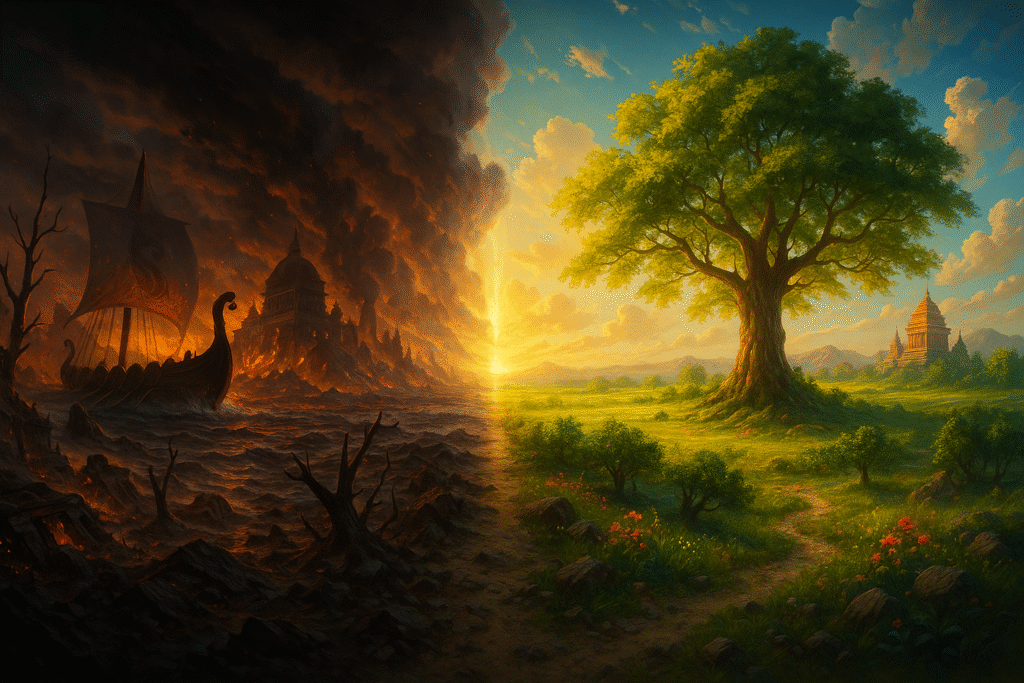

A lone warrior stares at a darkening sky as flames devour the earth, while in another realm, a divine horseman gallops forth to end an age of darkness. These are not fragments of a single tale, but vivid echoes from end-of-world myths across cultures. From ancient India to the icy north, civilizations have imagined a dramatic Armageddon—cosmic destruction followed by renewal. These powerful narratives share a paradoxical truth: every ending holds the seed of a new beginning.

Why are end-of-world myths so widespread? What do a Hindu sage’s prophecy, a Norse poet’s tale, and a Biblical narrative of flood all have in common? In this post, we’ll journey through some of the world’s most captivating apocalypse myths – from the Hindu Kali Yuga and Norse Ragnarök to Biblical and Aztec cataclysms. As we compare these tales, striking parallels emerge. Each culture’s “Armageddon” brings not just destruction, but also hope: the idea that light follows darkness, and a shattered world can be reborn anew.

Are these myths purely fantasy, or do they reflect something deep about the human psyche and the cycles of history? Let’s explore these apocalyptic visions across cultures and see what they reveal about our collective longing for renewal after devastation.

Table of Contents

- Hinduism: Kali Yuga’s End and the Promise of Renewal

- Norse Mythology: Ragnarök – The Viking Apocalypse

- Biblical Myths: The Great Flood and the Final Apocalypse

- Mesoamerican Myths: Aztec Five Suns and Mayan Cycles

- Zoroastrianism: The Final Battle and Renewal in Persian Lore

- Common Threads and Real-World Reflections

- Conclusion: After Darkness, Light

- FAQ

References & Further Reading

Hinduism: Kali Yuga’s End and the Promise of Renewal

In Hindu cosmology, time moves in vast cycles of four ages (Yugas) from perfect virtue to deep darkness. We are currently in the fourth and darkest age, Kali Yuga, an era of strife, ignorance, and moral decline. But Hindu scriptures comfortingly predict that even this dark age will end. As evil peaks and “dharma” (righteousness) nearly disappears, a dramatic restoration awaits.

According to ancient texts like the Mahabharata and Puranas, Kali Yuga will climax in chaos and unrighteousness – a time when “the kings become thieves and society crumbles.” At this nadir, Vishnu’s prophesied final avatar, Lord Kalki, will appear to destroy the forces of adharma (evil) and usher in a new golden age. Mounted on a white horse and wielding a blazing sword, Kalki is said to cut down the wicked and renew the world. As one scripture foretells:

“When the earth is overrun with evildoers, Lord Vishnu will incarnate as Kalki to destroy the wicked and restore righteousness.” – Bhagavata Purana 12.2.19

After this apocalyptic purification, the cycle starts afresh with Satya Yuga, the Age of Truth. In essence, the end of Kali Yuga is not final – it’s a cosmic reset that brings back virtue and harmony. Hindu thought emphasizes cyclical time; creation, destruction, and rebirth form an eternal wheel. (See our article on the Four Yugas for a deeper dive into Hindu time cycles.)

Interestingly, Hindu mythology even contains a great flood story of its own: the tale of Manu and the Matsya (Fish) Avatar. Much like Noah, Manu is warned of a world-ending flood and saves humanity by preserving life in a huge boat. (In fact, Hindu lore’s great deluge parallels the Biblical flood – see our post on Manu’s Deluge to explore that connection.) This reinforces the theme that after a catastrophic purge (be it flood or Kalki’s fiery sword), life is renewed under divine guidance.Hindu End-Time in a Nutshell: A dark age of quarrel ends with a divine intervention. Kalki’s apocalypse eradicates evil and resets Dharma, proving that even in a cyclical universe, the end of the world is a new beginning.

Norse Mythology: Ragnarök – The Viking Apocalypse

Travel now to the frozen north, where Viking skalds sang of Ragnarök, the doom of gods and men. In Norse mythology, Ragnarök is the gripping tale of how the current world will end in a ferocious final battle and natural catastrophe – yet from this ruin a new world will rise. The word Ragnarök literally means “fate of the gods” or “twilight of the gods” – and indeed even Odin, Thor, and Loki meet their destinies in this myth.

The saga unfolds with worsening omens: the beloved god Balder’s death, followed by the Fimbulwinter – three years of unending winter. Brothers turn against brothers, and humanity descends into war. Monsters break free: the colossal wolf Fenrir snaps his chains, the Midgard Serpent Jörmungandr rises from the sea, and fire giants led by Surtr surge forth. The very sky splits as evil forces assault the gods’ stronghold. The mighty Odin battles Fenrir and is devoured; Thor succeeds in slaying the serpent but dies from its venom; nearly all gods and giants perish in the epic clash. Finally, Surtr’s flames consume the earth. The old world sinks into the sea, dark and lifeless.

Yet Ragnarök is far from a nihilistic end. In the Norse vision, destruction paves way for renewal. After the world burns and submerges, the earth is reborn from the waters. A few gods survive or return – Odin’s sons Vidar and Vali live on, Thor’s sons inherit his hammer, and the once-slain Balder comes back from Hel. Two humble human survivors, Líf and Lífthrasir, emerge from the shelter of the World Tree Yggdrasil, having weathered the cataclysm. They will repopulate the renewed earth, under the gentle rule of the new generation of gods. One haunting Norse verse paints this cycle of annihilation and rebirth:

“The sun turns black, earth sinks into the sea… yet from the sea the earth rises green once more.” – Poetic Edda (Völuspá)

Thus, the Viking apocalypse ends with hope: a green world born anew from the ocean, cleansed of the old strife. Time in Norse myth may not be endlessly repetitive like the Hindu yugas, but Ragnarök shows a belief in cyclic regeneration nonetheless. The old order falls so a fresher, purer world can begin, implying that even gods are bound to cycles of death and rebirth.It’s fascinating that a culture of warriors and seafarers imagined their world’s end as an all-consuming war followed by the earth literally rising from the sea. Ragnarök’s dramatic imagery of cosmic battle and renewal has inspired countless stories – from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung opera to modern Marvel movies – underscoring the enduring appeal of this end-of-world myth.

Biblical Myths: The Great Flood and the Final Apocalypse

The Western/Abrahamic tradition offers its own powerful visions of the end. In the Judeo-Christian Bible, we find both an ancient world-ending flood and a prophecy of a final cosmic showdown often referred to as Armageddon. These narratives shaped the very word “apocalypse” (from Greek apokalypsis, meaning revelation) and continue to influence how many view the idea of an end times.

The Great Flood: In the Book of Genesis, God, finding humanity steeped in violence and sin, decides to reset the world with a colossal flood. He spares only the righteous Noah, his family, and pairs of all creatures aboard the ark. For forty days, waters drown every other living thing – essentially an apocalypse by water. When the flood subsides, it’s a new dawn for creation. Noah’s family repopulates the cleansed earth, and God makes a covenant (symbolized by the rainbow) never to destroy the world by flood again. This flood myth, like many others, emphasizes destruction as divine cleansing and the survival of a chosen seed to restart humanity. (Intriguingly, flood legends abound worldwide – from Mesopotamian Utnapishtim to India’s Manu – hinting at either a shared memory or a common storytelling motif of renewal after deluge.)

Armageddon and the Final Battle: The New Testament, particularly the Book of Revelation, describes a dramatic end-of-world battle between the forces of good and evil. The term Armageddon has come to denote this ultimate conflict. In Revelation’s vivid symbolism, plagues and wars ravage the earth, the Antichrist rises, and nations clash at Armageddon. Finally, Christ (a messianic savior figure) returns, defeats Satan and evil once and for all, and presides over a Last Judgment of souls. The current world passes away amidst earthquakes and fire, and then comes the promised renewal:

“Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away.” – Revelation 21:1

In this Christian vision, time is not cyclic but linear, moving toward a definitive conclusion and rebirth. The faithful are rewarded with a holy new world (“New Jerusalem”), and tears, death, and pain are no more. Similarly, in Islamic tradition (being an Abrahamic faith), the Day of Judgment (Qiyamah) portrays a final upheaval of the world, resurrection of the dead, judgment of all souls, and transition to an eternal afterlife.

What’s notable is the familiar pattern: widespread corruption leads to a divinely ordained catastrophe, which in turn leads to a fresh start for the world under divine order. The Biblical flood is a one-time reset of creation; the Christian apocalypse is a promised ultimate restoration of peace and justice. Both reinforce a moral message – that after punishment or purification comes mercy and renewal.

The word “Armageddon” itself has entered everyday language to mean any catastrophic confrontation, showing how deeply this mythic idea resonates. Even today, movies and books imagine doomsday scenarios and post-apocalyptic worlds, essentially retelling the old motif in modern guise. The enduring hope is that beyond the suffering of any “apocalypse” lies a chance to rebuild and start again.

Mesoamerican Myths: Aztec Five Suns and Mayan Cycles

Across the ocean in the Americas, ancient Mesoamerican civilizations had strikingly cyclical views of time and multiple world endings. The Aztecs, for example, believed that four worlds had existed and perished before the current one. Their myth of the Five Suns is essentially a series of apocalypses and rebirths: each “Sun” (world age) was ruled by different gods and ended in a cataclysm.

According to Aztec legend, the First Sun era ended when giants (the inhabitants of that age) were devoured by jaguars. The Second Sun was destroyed by ferocious winds, turning people into monkeys. The Third Sun fell to fire and volcanic rain, and the Fourth Sun drowned in a great flood, with humans transformed into fish. Each time, a few life forms survived or were transformed, allowing the world to be remade. The Aztecs saw themselves living under the Fifth Sun, which, ominously, was destined to end in a devastating earthquake. In fact, the Aztec word for the current age, Nahui-Ollin (4-Movement), indicates movement or earthquake as the future doom of this world. They believed the sun god needed regular human blood offerings to stay strong and delay this end – a dramatic example of a culture taking active role to postpone their apocalypse.

This cycle of creations and destructions shows a profound acceptance that worlds come and go in phases. The Aztecs even performed a New Fire Ceremony every 52 years (the completion of a calendar round), essentially a mini-ritual of renewal to ensure the world wouldn’t end at that cycle’s close. People would extinguish all fires, gaze at the stars to see if the cosmos remained on course, and then rekindle the fire – symbolizing the rebirth of the world for another cycle.

The Maya civilization, culturally related to the Aztecs, had a similar concept of great cycles. The Maya Long Count calendar famously “ended” a 5,125-year cycle on December 21, 2012, which some modern interpretations (and pop culture) mistook as a prediction of the end of the world. In truth, Maya texts suggest it was the end of one baktun cycle and the start of another – a transition, not a termination. The Maya also told stories (e.g., in the Popol Vuh) of previous failed creations of humanity (made of mud, then wood, etc.) which were destroyed, before the successful creation of people made of maize. Again, the theme of multiple tries, multiple destructions, and finally a lasting world appears.

What’s fascinating is how much Mesoamerican myths mirror Old World ones despite independent development. The Aztec Fourth Sun perishing in a flood parallels flood myths from Noah to Manu. Their belief in a forthcoming earthquake apocalypse echoes other cultures’ prophesied end by quakes or fire. And like Hindus, they saw time as an unending wheel of ages. To the Aztecs and Maya, the end of a world was not final extinction but part of a grand cosmic schedule.In these cultures, we also see human agency intertwined with myth – the idea that rituals and righteous living could stave off or prepare for the apocalypse. Sacrifices to the sun, or cleansing ceremonies at calendar’s end, were ways to keep the cosmic order running and push the ultimate end further into the future.

Zoroastrianism: The Final Battle and Renewal in Persian Lore

Moving to ancient Persia, we find one of the world’s oldest apocalyptic visions in Zoroastrianism. Long before Revelation was written, Zoroastrian scriptures (and later Pahlavi texts) described a cosmic struggle between good and evil that culminates in a final renovation of the world. This concept, called Frashokereti in Avestan, is the ultimate triumph of good and the making fresh of the world.

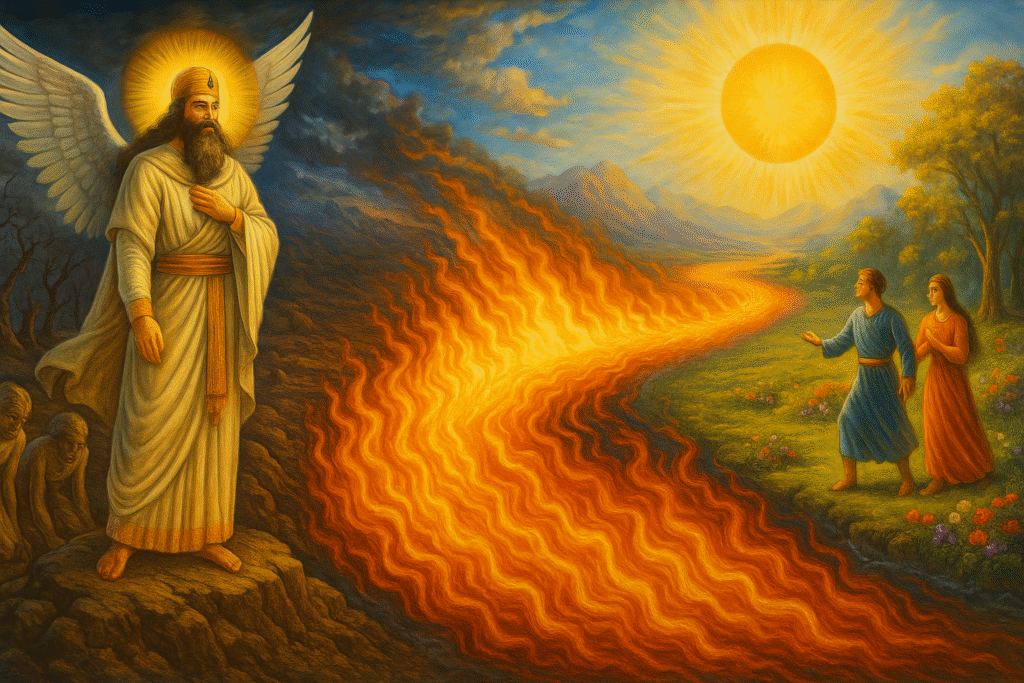

Zoroastrian cosmology divides time into epochs, including a final age when a savior-figure called Saoshyant will arrive. As evil reaches its peak, Saoshyant (literally “one who brings benefit”) leads the forces of good in a last battle against the demonic forces of Angra Mainyu (the evil spirit). This showdown has striking similarities to the later Abrahamic apocalypse: the dead will be resurrected (a concept Zoroastrianism was among the first to introduce), and a Last Judgment of souls occurs. Every person must wade through a river of molten metal; for the righteous it feels like warm milk, but the wicked burn – a vivid metaphor for purgation of sin. In the end, even the souls in hell are purified and released. Evil is completely destroyed and banished from the cosmos.

What follows is a perfect world, restored to the pristine state of creation. The Zoroastrian texts describe a kind of heaven on earth: no more hunger, thirst, illness, or death, and humans become immortal and at peace. All souls united, all worshiping the supreme god Ahura Mazda in a harmonious existence – time itself ends as the purpose of creation is fulfilled. This is not a cyclic restart but a final resolution of the cosmic story.

Notably, Zoroastrianism’s end-time ideas likely influenced Jewish, Christian, and Islamic eschatology (owing to cultural contact in ancient times). Concepts like a single great judgment, resurrection, and a messianic savior bringing world peace have clear echoes. For our comparative theme, the takeaway is: destruction leading to ultimate renewal is again central. Here the emphasis is ethical and cosmic – the victory of good over evil once and for all – yet it still follows the pattern of a cataclysm (the earth melting in fire) followed by a new, purified existence.

The resonance with other myths is uncanny. Fire as a cleansing force appears in Norse (Surtr’s flames), in Hindu lore (the fiery end of the yuga), in some Christian visions (the world ending in fire next time, not flood). A savior figure appears in Zoroastrian (Saoshyant), Hindu (Kalki), Christian (Second Coming of Christ), even in some interpretations of Norse (Balder returning as a kind of reborn hope). It’s a reminder that across cultures, people longed for a deliverer to save the world from chaos and usher in an era of peace.In essence, Zoroastrianism’s apocalypse is a promise that history has a happy finale: after a period of trial, truth and goodness will remake the world into a blissful paradise. It’s an early expression of a fundamentally optimistic cosmology wrapped in an end-of-world narrative.

Common Threads and Real-World Reflections

Exploring these diverse myths side by side, we can’t help but notice common threads. Despite arising in different eras and places, Hindu, Norse, Biblical, Mesoamerican, and Persian traditions (among others) envision very similar end-of-world scenarios:

- A Moral Decline: Most myths begin with the world falling into decay – whether it’s the rampant adharma of Kali Yuga, the treachery and kin-slaying before Ragnarök, the wickedness before the Flood, or humanity’s corruption in various legends. This reflects a shared idea that extreme moral chaos triggers cosmic reset.

- A Cataclysmic Event: The form differs (flood, fire, war, earthquake, winter), but there is always a massive catastrophe that wipes the slate clean. Floods are especially widespread in myths, possibly echoing real ancient floods or simply symbolizing cleansing. Fire and battle serve a similar purging role in other cultures.

- A Chosen Survivor or Savior: Many stories have either a heroic survivor (Noah, Manu, Lif and Lifthrasir) or a savior figure (Kalki, Christ’s return, Saoshyant) – or both – who ensure continuity into the next world. The presence of a savior/guide reassures believers that the destruction is part of a plan, not random doom.

- Renewal and Hope: Crucially, the apocalypse is never the ultimate end. There is always a renewal – a new world, a new age, a cleansed Earth. In fact, these could be seen not as “end of the world” myths but “end of an age” myths. The cycle or story continues, often in a better state than before. This imparts a hopeful lesson: even the worst catastrophe can lead to fresh growth.

Why might such narratives be nearly universal? Some scholars suggest that ancient peoples, observing natural cycles (seasons, day/night, life/death) and catastrophic events (floods, volcanic eruptions, eclipses), intuited that creation and destruction go hand in hand. Psychologically, these myths may address a deep human fear of the unknown end, turning it into a story with meaning and even a positive outcome. They offer comfort that darkness is followed by dawn. In times of crisis – be it plagues, war, or societal collapse – communities could find solace in the idea that “this too shall pass” and a new era will emerge.

There are also real-world historical reflections of this cycle. Civilizations have risen, fallen in turmoil, and given birth to new societies. For instance, the fall of Rome (often described in apocalyptic terms by contemporaries) led to the medieval world and eventually the Renaissance – literally a “rebirth” of culture. In Eastern philosophy, the concept of samsara (cycle of birth and rebirth) and even the rise and fall of dynasties reflect a similar rhythm. We might say these myths externalize a pattern that humanity has observed time and again: after upheaval comes rebuilding.

On a personal level, end-of-world myths can also be seen as metaphors for individual transformation. We sometimes undergo our own “apocalypses” – the end of a way of life, a crisis that turns everything upside down – only to come out the other side changed and with a new start. The promise of light after darkness can be deeply inspiring in such moments.

Modern culture continues to recycle these themes. Apocalyptic movies (from alien invasions to zombie outbreaks) almost always conclude with survivors forging a new hope. Environmental discussions use doomsday imagery (a “climate apocalypse”) but also stress that human action can still save the future – reminiscent of rituals to prevent the end. Our storytelling instinct remains drawn to imagining the worst, and imagining what comes after the worst.In sum, the uncanny parallels in these myths remind us that despite differences in details, human cultures share a profound optimism wrapped in tales of destruction. We prepare for the worst but inherently believe in a cycle of renewal. It’s a testament to an enduring truth: the end of one story is always the beginning of another.

Conclusion: After Darkness, Light

From the Kali Yuga in India to Ragnarök in Scandinavia, from the Biblical Armageddon to the Aztec Fifth Sun, the world’s end-of-world myths paint a dramatic yet reassuring picture. Yes, the old world must crumble – whether through divine judgment, heroic sacrifice, or natural cataclysm – but something pure and new always springs from the ruins. This cyclic view of destruction and rebirth seems almost woven into the human imagination.

Why do these stories endure? Perhaps they remind us that no defeat is final, and no night lasts forever. Just as heroes in myth bravely face the end, we too find courage in the idea that beyond our greatest challenges lies a new morning. The light after darkness motif resonates with our deepest hopes. It teaches patience and faith: even when it feels like the “end of the world,” it may, in fact, be the incubation of a new beginning.

In the rich lore of Vedic traditions, as well as in Viking sagas and holy scriptures, there’s a shared moral: hold onto righteousness and hope, even amidst doom. In many myths, those who stay true (the righteous Noah, the pious Manu, the worthy souls awaiting Saoshyant) are the ones who inherit the next world. Valor, faith, and moral leadership become the torches that carry humanity through the darkness. (This aligns beautifully with the ethos of VedicWars – where valor and wisdom ultimately triumph over chaos.)Ultimately, “Armageddons Across Cultures” aren’t just about worlds ending in fire or flood. They’re about renewal – on cosmic and personal levels. They encourage us to be resilient, to learn from the past cycles of history, and to become agents of positive rebirth in our own time. As the saying goes, “Every ending is a new beginning.” The ancients understood this well. In their imaginative warnings and prophecies, they left us not only tales of destruction but a powerful message of trust, unity, and renewal for generations to come.

FAQ

Q1: Do all cultures have an apocalypse myth or end-of-world story?

A: Not every single culture, but many cultures worldwide do have myths about a great ending. These range from floods and fires to final battles. The prevalence of such stories – from Mesopotamia’s flood epics to the Maori myths of world cycles – suggests a common human fascination with how the world might dramatically transform or end. Some cultures without a singular apocalypse myth still often have cycles of ages or prophesies of transformative events. Overall, the theme of an “end times” followed by renewal is one of the most widespread in mythology.

Q2: How is the Hindu Kali Yuga timeline different from, say, the Christian end times?

A: Hinduism sees time as cyclical. Kali Yuga is the last phase of a cycle that will definitely end, but it will be followed by the restart of a golden age (Satya Yuga). This cycle repeats over vast cosmic timescales. In contrast, the Christian (and Islamic/Jewish) end times are generally linear – a one-time end of this world, leading into an eternal afterlife or divine kingdom (a new heaven and earth). Additionally, Kali Yuga is a long age (432,000 years according to tradition, with many years still to go), whereas some Christian interpretations see the end times as imminent or tied to moral/spiritual conditions rather than a fixed cosmic schedule. Both feature a lot of turmoil and a savior figure (Kalki or Christ) but the framework of time differs.

Q3: Are these end-of-world myths meant to be taken literally, or are they symbolic?

A: It depends on whom you ask. Traditionally, believers of those cultures often took them as real future events (or past events, in the case of floods). For example, Norse devotees likely expected Ragnarök to happen someday. However, many myths also function on a symbolic or philosophical level. The destruction can symbolize purging of evil, and the renewal symbolizes hope and moral rebirth. Modern scholars and spiritual interpreters often read these stories metaphorically – as allegories about the cyclic nature of life, the triumph of good over evil, or even internal spiritual transformation (the “end of the world” of ego leading to an enlightened state, for instance). In essence, they carry moral and existential lessons regardless of literal truth.

Q4: What are some lesser-known apocalypse myths not covered in detail here?

A: There are many! For instance, ancient Egyptian mythology didn’t have a clear one-time apocalypse, but they feared the sun god Ra might eventually stop his daily journey, plunging the world into darkness – a kind of eternal night. In Hopi Native American tradition, we’re said to be in the Fourth World, with previous ones destroyed by flood and fire; a future purification is expected as we transition to a Fifth World. Hesiod’s Greek myth of five ages (Gold to Iron) isn’t an apocalypse per se, but it implies the current Iron Age will end when humans no longer uphold justice, perhaps leading Zeus to wipe the slate. Also, Buddhism speaks of cycles where the Dharma declines and then is revived by future Buddhas (Maitreya being the next) – a more spiritual “renewal” concept. Each culture’s version has unique twists, but the pattern of decline – destruction – renewal appears in many forms.Q5: What’s the significance of cycles in these myths – why do so many emphasize a cyclic time?

A: Emphasizing cycles helps convey that endings are not permanent. In a world of observable natural cycles (seasons, day/night, lunar phases), it may have felt intuitive to ancient people that time itself works in circles. A cyclical worldview is comforting because it promises that after an ending, a beginning will come. It also imposes a kind of order and predictability on the cosmos – things happen in grand repeating patterns, perhaps under divine orchestration. Moreover, cycles reinforce moral lessons: if we’re in a downtrend (like Kali Yuga or the Aztec 52-year cycle’s end), we know a fresh start will come, but also that our actions in each cycle matter (to bridge into the next). Even the linear end-of-days myths often borrow from cyclical thinking by adding a reboot (e.g., a 1000-year reign of peace after Armageddon, or an eternal heaven – essentially a new “cycle” that doesn’t end). It’s a way of saying the story never truly ends – it just enters a new chapter.

References & Further Reading

- Hindu Scriptures (Puranas & Itihasas): Descriptions of Kali Yuga and Kalki can be found in texts like the Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana (Srimad Bhagavatam, Canto 12) – which detail how Kalki ends the age of darkness and restores Dharma. The Mahabharata (esp. the Shanti Parva) also discusses Yuga cycles.

- Poetic Edda (Norse Mythology): Particularly the poem Völuspá gives a vivid account of Ragnarök – including the fall of gods and the rebirth of the world. Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda (13th century) retells this myth in detail.

- Bible (Old & New Testament): The story of Noah’s Flood is in Genesis 6-9. Apocalyptic prophecies are found throughout the Bible, especially in Revelation (for the final battle and new world) and in prophetic books like Daniel or Isaiah. The Book of Enoch (an ancient Jewish text) also has fascinating end-time visions.

- Aztec & Mayan Sources: Look into the translated codices and chronicles. The Aztec “Legend of the Five Suns” is recorded in sources like the Codex Chimalpopoca. For a readable overview, see “The Legend of the Fifth Sun” (ThoughtCo, 2025) by Nicoletta Maestri, and the World History Encyclopedia’s entry on Five Suns. Maya beliefs about cycles can be found in the Popol Vuh and in studies of the Maya calendar (e.g., Linda Schele’s work).

- Zoroastrian Texts: The concept of Frashokereti and the role of Saoshyant are described in the Pahlavi text Bundahishn and hinted in the Avesta. For a summary, Encyclopedia Iranica or Britannica’s section on Zoroastrian eschatology are good starting points.

- Comparative Analyses: For those interested in more academic comparisons, consider works like Mircea Eliade’s “Cosmos and History” which discusses cyclic time, or Joseph Campbell’s discussions on apocalyptic myths in “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”. These explore the psychological and symbolic underpinnings common to these narratives.

(Feel free to explore the above sources for a deeper understanding of each myth. They offer rich details far beyond the scope of this single article, and underscore how cultures separated by oceans and millennia still converged on the profound idea of Armageddons followed by renewal.)