Ramayana Abroad might sound like a modern travelogue, but it actually describes an ancient journey. Picture this: deep in the Cambodian jungle at Angkor, a stone carving shows Prince Rama’s monkey army battling a demon king – a scene straight out of the Indian epic Ramayana. Yet we’re not in India at all. From the temples of Cambodia to the royal courts of Thailand and Indonesia, Ramayana Abroad is the story of how India’s beloved epic and its divine legends voyaged across the seas and took root in faraway lands. It’s a journey of culture and faith carried by traders, priests, and kings – revealing a shared heritage that transcends borders.

Why does this ancient Ramayana Abroad tale matter today? Because discovering familiar epics in unfamiliar places is like finding family in a foreign land. It shows how deeply myths can connect distant peoples. As we explore how the Ramayana and the lore of gods like Shiva spread to Southeast Asia, we uncover lost tales of adaptation, local twists, and enduring devotion. These stories of a shared heritage remind us that our legends – much like humanity – have always been travelers at heart.

Table of Contents

- Ramayana Abroad: A Journey Across the Seas – How Indian epics sailed beyond India’s shores.

- Ramayana Abroad in Cambodia: Angkor’s Lost Tale – The epic’s imprint on Khmer temples and art.

- Ramayana Abroad in Thailand & Indonesia – Local twists in the Thai Ramakien and Javanese tales.

- Shiva Abroad: God-Kings and Sacred Mountains – How Shiva’s cult and cosmic mountain lore spread.

- FAQs on Ramayana Abroad – Your questions answered about the epic’s global journey.

- Conclusion – Reflecting on the shared mythic heritage and why it endures.

Ramayana Abroad: A Journey Across the Seas

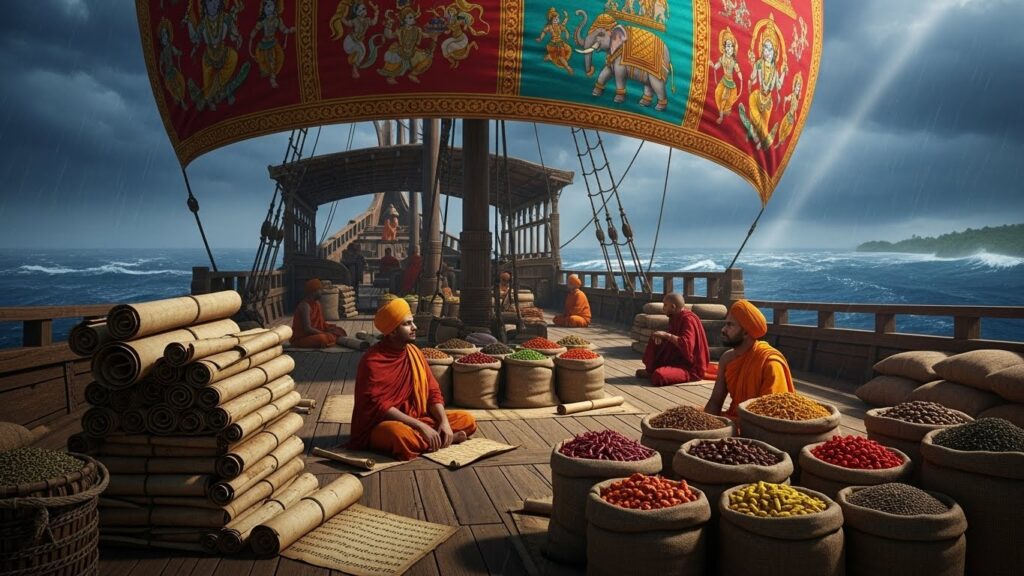

How did Ramayana stories end up engraved in Cambodian stone or danced on Balinese stages? The answer lies in ancient oceans and adventurous souls. Over 1,500 years ago, Indian merchants and Brahmin priests set sail with the monsoon winds, carrying more than spices and silk. They also carried stories and gods in their hearts devdutt.com.

As seasonal trade winds blew across the Indian Ocean, ships ferried India’s epics to port cities in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia devdutt.comdevdutt.com. Along these busy trade routes, local kings welcomed Indian sages, artists, and traders – embracing the new tales and traditions they brought.

One legend speaks of an Indian sage, Kaundinya, who married a naga princess in the Mekong delta (ancient Funan) and became king, blending Indian and local traditions devdutt.com. Such tales symbolize how Ramayana Abroad took hold: through cultural exchange, marriage alliances, and the allure of India’s wisdom. Over centuries, Southeast Asian courts eagerly adopted Hindu epics.

Why? The Ramayana’s themes of righteousness and devotion resonated universally. Local poets translated and retold the epic in their own languages, while artists gave the characters regional features and dress. This is why we find Rama, Sita, Hanuman, and Ravana not only in Sanskrit verses, but in Khmer, Thai, Javanese, Lao, and Malay folklore – each with a unique accent.Crucially, Indian epics also offered a kind of political and spiritual legitimacy.

Ancient kings saw themselves in these divine stories. By associating with Rama (the ideal king) or invoking gods like Shiva and Vishnu, Southeast Asian rulers enhanced their authority. They built temples and inscribed epics on stone to proclaim, “We too are part of this sacred story.” Ramayana Abroad thus became a tool of soft power and devotion alike – a shared cultural language from India to Asia’s far corners.

An artistic impression of an ancient ship braving monsoon winds, much like those that once ferried Indian storytellers and sages to foreign shores. Such voyages helped carry the Ramayana abroad, spreading India’s epics and gods to distant kingdoms devdutt.com. The sea routes became highways of both commerce and culture, ensuring the Ramayana Abroad saga would unfold across Southeast Asia.

Ramayana Abroad in Cambodia: Angkor’s Lost Tale

Cambodia guards one of the most breathtaking chapters of the Ramayana Abroad. At Angkor – the heart of the medieval Khmer empire – the Indian epic is literally written in stone. The Khmer version of Ramayana, known as Reamker (“Glory of Rama”), thrived under Cambodian kings. Walk through Angkor Wat’s temple galleries and you’ll find entire walls carved with familiar scenes: Hanuman leading an army of monkeys, the demon king Ravana with ten heads and twenty arms, Prince Rama firing his bow, and Sita in captivity.

One spectacular bas-relief on Angkor Wat’s western wall depicts the climactic Battle of Lanka, with Rama’s forces of monkey-warriors clashing against Ravana’s rakshasa demons. Elsewhere, carvings show the golden deer tricking Sita and the vulture Jatayu bravely fighting Ravana – moments lifted straight from Valmiki’s Sanskrit Ramayana and immortalized by Khmer artisans in the 12th century.

Why did the Khmer emperors immortalize Reamker in their holy city? The answer lies in power and faith. The Khmer kings, who styled themselves devaraja (god-kings), saw epic tales as more than entertainment – they were divine models for rulership. By aligning themselves with Rama’s righteousness and Vishnu’s protection, the kings bolstered their own legitimacy. King Suryavarman II, who built Angkor Wat, dedicated it to Vishnu and perhaps saw echoes of Vishnu’s avatar Rama in his own rule.

These kings commissioned intricate bas-reliefs to adorn temple walls, effectively carving their favorite myths into Cambodia’s very landscape. The result was a breathtaking fusion of art and mythology: Angkor’s stones speak Sanskrit without using any script, narrating Ramayana episodes to all who pass.What makes Cambodia’s Ramayana Abroad tale even more fascinating are the local twists of the Reamker.

In Cambodian dance dramas and shadow puppetry (called Sbek Thom), the story absorbed Buddhist influences and Khmer folklore. For instance, Cambodian renditions often portray Rama and Sita as more human and fallible, emphasizing moral lessons in line with local beliefs. The Reamker adds episodes not found in Valmiki’s original, and characters like Hanuman may have expanded roles – becoming folk heroes with a bit of mischievous charm. Even today, Reamker dance performances remain a proud part of Cambodian culture, proving that the tale lives on beyond temple stones.

A scene from Cambodia’s Angkor temples brings Ramayana Abroad to life: here, Rama’s monkey army is carved in sandstone, charging into battle. The Khmer sculptors captured the energy of the epic – you can almost hear the clash of armies in this bas-relief. Such carvings at Angkor Wat and Bayon stand as a testament to how deeply the Ramayana took root in Cambodian art. The epic became part of Khmer identity, with Angkor’s kings literally inscribing Rama’s story abroad into their sacred architecture.

Ramayana Abroad in Thailand & Indonesia: Local Twists on a Global Epic

The Ramayana’s journey didn’t stop at Cambodia. In Thailand, the epic blossomed into the Ramakien, the Thai national epic. Centuries ago, Thai kings adopted the Ramayana and gave it a Siamese soul. They renamed the hero Phra Ram, his wife Nang Sida, and the demon Totsakan (Ravana). The outline remained Indian – a prince’s quest to rescue his queen – but the flavors became local. The Ramakien is famously depicted in the murals of Bangkok’s Grand Palace: 178 vivid panels showing everything from the abduction of Sita to Hanuman’s exploits.

Thai artists, under King Rama I, painted these scenes with glittering detail – golden-armored warriors, multi-headed demons, and Hanuman portrayed as a white monkey god who can grow giant or vanish at will. Notably, Thai tradition sometimes gives Hanuman a playful, amorous personality (a unique twist, as in Valmiki’s version Hanuman is celibate). This highlights how Ramayana Abroad was not a static import; it was joyfully adapted to fit Thai culture and Buddhist values. Even the ending of Ramakien can differ – in some Thai tellings, Sita is reclaimed without a fire test, aligning with local sensibilities of compassion.

Indonesia has its own rich chapter of Ramayana Abroad. On the island of Java, poets in the ancient Javanese court composed the Kakawin Ramayana around the 9th century, blending Sanskrit verses with Javanese meteresamskriti.com. This version includes extra adventures and a pronounced role for a wise ogress character unique to Java. The influence of the epic is also etched in Java’s greatest Hindu temples. At Prambanan – a massive 9th-century temple dedicated to Shiva – the inner walls are lined with Ramayana reliefs.

As you walk the corridors of Prambanan’s Shiva temple, you can follow the story panel by panel: Sita’s abduction, the burning of Lanka, Hanuman meeting Sita, and Rama’s final victory, all carved in volcanic stone. Javanese dancers meanwhile developed their own interpretations – like the Ramayana ballet still performed by moonlight at Prambanan, where traditional gamelan music accompanies performers playing Rama, Sita, and Ravana in elaborate gold and batik costumes.

Other Southeast Asian cultures have their Ramayana versions too. In Laos, the tale is called Phra Lak Phra Lam (after Lakshmana and Rama)esamskriti.com. In Myanmar (Burma), it’s the Yama Zatdaw, often staged as a dance drama. Each retelling modified names and details: Lakshmana became Lak or Laksaman, and Ravana sometimes gained new backstories.

Yet, remarkably, the core values of the epic – dharma (righteousness), loyalty, and the triumph of good over evil – stayed intact across every borderesamskriti.com. This shows the universal appeal of the Ramayana. Whether in a Thai monastery, a Balinese village, or a royal Cambodian court, people saw their own struggles and hopes reflected in Rama’s exile, Sita’s purity, or Hanuman’s devotion.

Above: A colorful mural from Bangkok’s Wat Phra Kaew temple illustrates the Ramakien, Thailand’s take on the Ramayana. Here, Rama and Hanuman charge into battle against Ravana’s forces, painted in rich detail. Meanwhile in Java, Indonesia (below), the Prambanan temple’s stone carvings retell the epic in another medium – you can see a relief of Rama confronting demon warriors commons.wikimedia.orgesamskriti.com. These images show the Ramayana abroad in full glory: embraced in palaces and temples far from its Indian birthplace, yet lovingly preserved through local art and storytelling.

In Java’s Prambanan temple, Ramayana Abroad takes form in stone. This bas-relief shows Prince Rama (center) battling the demon Subahu, watched by Lakshmana and sages, as described in Javanese Ramayana lore. Javanese sculptors carved these panels over a thousand years ago, blending Indian narrative with local craftsmanship. The continued reverence for such reliefs and the popularity of Ramayana dance dramas in Indonesia today underscore the epic’s enduring footprint across Asia esamskriti.com.

Shiva Abroad: God-Kings and Sacred Mountains

It wasn’t just the Ramayana that traveled; the gods themselves went abroad. Among them, Lord Shiva – the mighty ascetic and cosmic dancer – found particularly fervent adoption in Southeast Asia. This spread of Shiva’s cult is a vital part of the Ramayana Abroad era, because understanding it reveals why epics and temples flourished overseas. After the 7th century, a wave of Shaivism (worship of Shiva) swept through Indonesia and Cambodia.

Shaiva teachers taught local kings that a ruler could become an earthly embodiment of Shiva’s power – a concept known as the Devaraja (god-king). If a king performed the proper rituals, fasting and devotion, Shiva would infuse him with divine energy to protect and prosper the kingdom. This idea was revolutionary: it turned royal courts into holy ground and kings into living gods.

Cambodia’s Khmer empire provides a dramatic example. In the 10th century, King Jayavarman IV broke away from Angkor and established a new capital in the remote north. There, at a site called Koh Ker, he undertook an audacious project: to replicate Mount Kailasa (Shiva’s sacred mountain) on Cambodian soil. Jayavarman IV built a massive seven-tiered pyramid temple (Prasat Thom) rising 36 meters high – a man-made mountain intended as Shiva’s abode.

On its summit he placed a giant Shiva linga (phallic symbol of Shiva), effectively planting the axis of the universe in his kingdom. At Koh Ker’s foot, he dug a vast baray (water reservoir) to stand in for the River Ganga, and he carved riverbeds with countless lingas so that flowing water would be sanctified as it passed over them devdutt.com. The message was clear: Shiva, the Lord of Kailasa, now ruled in Cambodia, and the king was His chosen vessel devdutt.com.

All across Cambodia and Java, such sacred mountains rose. The famous Angkor Wat itself, though dedicated to Vishnu, is designed as a representation of Mount Meru (a cosmic mountain akin to Kailasa). Nearby, other Angkorian kings built temples like Phnom Bakheng and Pre Rup as temple-mountains. In Java, the grand temple of Prambanan (10th century) was likewise dedicated to Shiva and built to mimic a divine mountain soaring to the sky.

These structures weren’t public worship halls but ritual stages for the elite – places where kings would perform ceremonies to merge with Shiva’s essence . Priests chanted from the Shaiva Agamas (sacred texts) as incense and offerings filled the air, effectively “charging” the king with cosmic authority. Through these rites, the king became a Chakravarti (universal ruler) responsible for the kingdom’s harmony, rains, and fertility – an idea that further justified his absolute power.

What’s truly intriguing is how local cultures merged Shiva with indigenous beliefs. In Cambodia, Shiva was often worshipped alongside local nature spirits; in Thailand and Laos (though primarily Buddhist later), Hindu deities like Shiva and Vishnu were respected as powerful guardian spirits. Hinduism and local animism blended seamlessly. We also see artistic hybrids: in both India and Southeast Asia, images of Harihara (a deity that is half-Shiva, half-Vishnu) became popular, embodying a theological harmony. This indicates that people didn’t see a conflict in embracing multiple divine traditions; rather, they expanded their pantheon.

By the 12th century, many of these kingdoms (Cambodia under Jayavarman VII, for instance) transitioned to Buddhism. Yet the legacy of Shiva’s era endured in their monuments and folklore. Even today, a visitor gazing up at Angkor’s towers or Java’s volcano-like temples can sense the ancient idea that Mount Meru or Mount Kailasa stands before them. In essence, the spread of Shiva’s worship abroad underpinned the spread of epics like the Ramayana – they traveled together. Kings who built Shiva’s temples also patronized Ramayana art, seeing both as affirmations of cosmic order. The epic gave moral narrative to the kingdom, and Shiva gave it divine sanction.

This striking pyramid temple is Koh Ker’s Prasat Thom in Cambodia – essentially a man-made Mount Kailasa. Built in the 10th century, its terraces once held a towering Shiva lingam on top. Jayavarman IV created this as a physical symbol that Shiva’s power had taken root abroad in Khmer land. The ruins still exude a stern majesty: a reminder of how far devotion traveled. The Ramayana Abroad story isn’t only about an epic’s journey; it’s about gods like Shiva being embraced in new realms. When you stand before Koh Ker’s pyramid, you witness the boldness of a king who declared his kingdom the center of the cosmos – a ghost of Shaiva power now swallowed by the jungle, yet still whispering of a time when myth and empire were one.

FAQs on Ramayana Abroad

Q: Which Southeast Asian countries have their own Ramayana?

A: Several! Ramayana took on local names: Cambodia’s Reamker, Thailand’s Ramakien, Indonesia’s Javanese Kakawin Ramayana, Laos’s Phra Lak Phra Lam, and Myanmar’s Yama Zatdaw, among others. Each country adapted the story to its culture, but all share the same core plot of Rama, Sita, and the battle against Ravana.

Q: How did the Ramayana spread to these far lands?

A: The epic spread through trade, travel, and translation. Indian traders and priests brought the story overseas as early as the 1st millennium CE. Royals then sponsored local language versions and performances. The Ramayana’s universal themes made it easy to embrace abroad.

Q: What is the Reamker in Cambodian culture?

A: The Reamker is Cambodia’s version of the Ramayana. It’s cherished as a classic of Khmer literature and arts. The Reamker incorporates Buddhist elements and Khmer folklore, and its scenes are famously carved on Angkor’s temples. It remains alive in Cambodian classical dance and shadow puppetry today.

Q: Why do Angkor Wat and other temples show Indian epics?

A: The Khmer kings used epic imagery to legitimize their rule and venerate the gods. Carving the Ramayana on temple walls was a sacred form of storytelling and statecraft. It signified that Cambodian kings were part of the divine narrative, bringing prosperity and cosmic order to their realm.

Q: Did local versions of Ramayana change the story?

A: Yes, in charming ways. While the skeleton of the tale remained, local storytellers added new episodes, humor, or moral twists. For example, Thailand’s Ramakien gives Hanuman a larger-than-life persona with romantic dalliances, and the ending can be less tragic. These changes made the epic resonate with local values while preserving its soul.

Conclusion

From the stone temples of Angkor to the painted palaces of Bangkok, the Ramayana Abroad story shows that myths know no boundaries. Indian epics and deities found new homes in Southeast Asia, not as strangers, but as kindred spirits to local legends. This journey of the Ramayana and Shiva’s lore across oceans is more than historical trivia – it’s a reminder of our interconnected humanity. It tells us that a tale born on the banks of the Sarayu River in India could inspire kings in Cambodia and villagers in Bali, weaving a tapestry of shared heritage across continents.

In our modern world, these “lost tales” abroad are being rediscovered and celebrated as bridges between cultures. They encourage us to look beyond borders and see the universal values that unite us. After all, whether in Sanskrit or Khmer or Thai, the victory of light over darkness and the virtue of honor and love speak to the human soul.

Ramayana Abroad is ultimately a tale of unity – a thrilling saga of how storytelling and spirituality can travel vast distances and time, yet remain as resonant as ever.“May the echoes of Rama’s name continue to inspire across the globe, just as they did ages ago in distant lands.” Feel the connection, and if these stories moved you, do share your own reflections. (See our article on “Ancient Indian Epics in World Cultures” for more.) Let’s keep this epic journey alive – the conversation, like the Ramayana, belongs to all of us.

📚 References: Sources Behind Ramayana Abroad

- National Museum of Cambodia – “Reamker: The Cambodian Ramayana”

An official archive on Cambodia’s Reamker, with visuals and commentary on Angkor Wat’s Ramayana reliefs and classical Khmer dance.

🔗 https://www.museum.gov.kh/reamker - Sheldon Pollock – The Language of the Gods in the World of Men (University of California Press)

A scholarly deep dive into how Sanskrit epics like the Ramayana were used by Southeast Asian rulers to project sacred kingship.

🔗 https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520260030/the-language-of-the-gods-in-the-world-of-men - George Coedès – The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (University of Hawaii Press)

A pioneering historical analysis on how Indian culture, epics, and religion were transmitted through trade and royal patronage.

🔗 https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/the-indianized-states-of-southeast-asia/ - UNESCO World Heritage Documentation – Angkor Wat & Prambanan

Official heritage listings with detailed documentation and gallery of the Ramayana panels in Cambodia and Indonesia.- Angkor Wat: 🔗 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/668

- Prambanan Temple: 🔗 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/642

- Devdutt Pattanaik – Myth = Mithya and Ramayana Abroad insights

Indian mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik offers fresh takes on Ramayana interpretations, especially cross-cultural transformations in Southeast Asia.

🔗 https://devdutt.com/articles/ramayana-in-south-east-asia/