Introduction: Indian mythology is often thought of as just the Ramayana and Mahabharata, but beyond these familiar epics lies a vast tapestry of forgotten sagas. Imagine a righteous queen whose fury scorches a city, or a humble sage whose verses reshape society — these stories pulse through lesser-known texts and folk traditions. Exploring them matters because each adds depth and colour to India’s cultural heritage, revealing new heroes and spiritual lessons outside the mainstream canon. From the fiery Kannaki in the Tamil epic Silappatikaram to the reformer Basavanna in the Basava Purana, these epics broaden our perspective on dharma, devotion, and destiny.

Table of Contents

- Tamil Epics in Indian Mythology

- South & Western Legends in Indian Mythology

- Northeast Legends in Indian Mythology

- Telugu & Odisha Legends in Indian Mythology

- Folk Tales & Puranic Lore

- FAQs

- Conclusion

Tamil Epics in Indian Mythology

Tamil literature boasts a tradition of five ancient epics (Aimperumkappiyam) predating modern religious divides. For example:

- Silappatikaram – A 1st-century CE epic by Ilango Adigal about Kannaki and Kovalan. It is the Tamil classic of chastity and rage. Kannaki, wrongly punished through her husband, goes on to curse the king of Madurai and becomes deified. Scholars call this epic “the Iliad of Tamil culture” because it blends drama, poetry and mythology in a tragic tale.

- Manimekalai – By Chithalai Sathanar (around 5th–6th c. CE), it follows Kannaki’s daughter, Manimekalai, who rejects royal life to become a Buddhist nun. In this story she studies all systems of faith and finds Buddhism “the most perfect religion”. Manimekalai’s journey shows female spiritual empowerment and presents Indian mythology infused with Buddhist philosophy.

- Civaka Cintamani – A 10th-century Jain epic by Tirutakkatevar, famous for introducing long verse forms (viruttham) into Tamil literature. It tells of the adventures of the hero Civaka and includes love and valor.

- Valayapathi (9th c.) and Kundalakesi (5th c.) – Lost or fragmentary Jain/Buddhist epics mentioned in tradition. These and the above show Indian mythology was shared by Jain, Buddhist and Hindu poets alike in Tamil history.

These epics are often grouped by theme: Silappatikaram, Manimekalai and Civaka Cintamani all explore complex female protagonists. Kannaki in Silappatikaram transforms from a devoted wife into a rage-driven avenger of injustice. Manimekalai’s heroine becomes an enlightened bikkhuni (Buddhist nun). Each story offers a different view on fate, devotion and moral action. Together they remind us that ancient Indian mythology includes more than just gods and kings; it includes ordinary people caught in extraordinary moral struggles (See our article on “Kannagi’s Legend” for more).

South and Western Legends in Indian Mythology

Beyond Tamil Nadu, southern India has its own epic cycles. In Karnataka literature, the poet Pampa (10th c.) composed two masterpieces: Adi Purana (c. 939 CE) and Vikramarjuna Vijaya or Pampa Bharata (941 CE). These Jain-inspired epics retell stories of the universe in a distinctly local style. As one scholar notes, “Kannada produced at least two works – Pampa Bharata (c.941) and Kumaravyasa Bharata (c.1425) – which can rank among the epics of the world”. The 15th-century Kumaravyasa Bharata is a devotional Kannada version of the Mahabharata, full of regional flavor and bhakti sentiment.

- Adi Purana (941 CE) – Jain epic of Lord Rishabha, by Adikavi Pampa.

- Pampa Bharata (941 CE) – Pampa’s epic on Arjuna, blending Sanskrit epic tradition with Kannada poetic meter.

- Kumaravyasa Bharata (15th c.) – A celebrated Kannada Mahabharata known for its lyrical beauty.

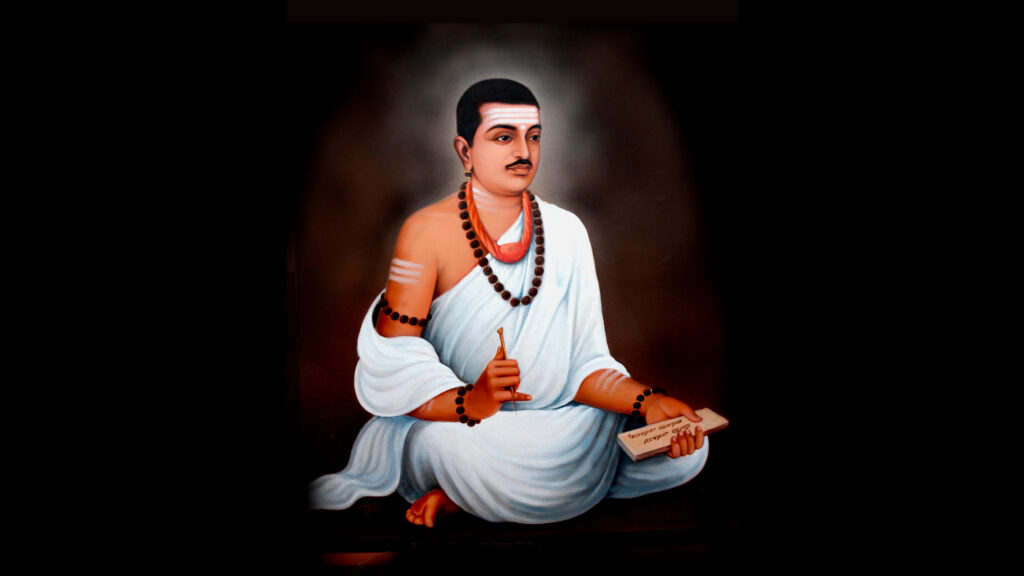

In neighboring regions, new heroes emerge. The Basava Purana (13th c., Telugu, by Palkuriki Somanatha) narrates the life of Basavanna (1134–1196 CE), the founder of the Lingayat (Veerashaiva) movement. It describes his defiance of caste and ritual as devotion to Shiva. A later Kannada translation (1369 CE by Bhima Kavi) became the standard biography of Basava. Basavanna is often honored as a saint-poet whose poetry (vachanas) preaches equality. His story shows Indian mythology from a social-reform perspective. (See our article on “Basavanna’s Lingayat Legacy” for more.)

Northeast Legends in Indian Mythology

Even India’s northeast has its epic sagas. In Assam, the 15th–16th century saint Srimanta Sankardev transcreated the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana into Assamese language. This work, simply called Bhagavat, is central to Assamese Vaishnavism. Sankardev also composed the Kirtan Ghosa, devotional songs narrating Krishna’s playfulness. These texts localize pan-Indian myths: for example, Krishna’s story is told in Assamese meter and uses local imagery. Such adaptations made mythology accessible to common people.

- Bhagavat of Sankardev (16th c.) – Assamese version of Bhagavata Purana, interwoven with Sankardev’s own verses.

- Kirtan Ghosa (16th c.) – A collection of Assamese devotional poems on Krishna.

In eastern India, the 15th-century Odia poet Sarala Das wrote an Odia Mahabharata, a creative retelling of the great epic in the local tongue. (He is revered as the “Adikabi” or first poet of Odia literature.) Though based on the Mahabharata, Sarala’s version reflects Odisha’s culture and values, adding folklore and local color. These regional epics illustrate how Indian mythology adapts to each land.

Telugu and Odisha Legends in Indian Mythology

Further south and east, other regional epics stand out. In Andhra Pradesh/Telangana, the 13th-century poet Palkuriki Somanatha (a Veerashaiva) wrote the Basava Purana (see above) in Telugu. Later, the 15th-century poet Bammera Pothana composed Andhra Maha Bhagavatamu, a highly revered Telugu version of the Bhagavata Purana dedicated to Lord Rama. Pothana refused royal patronage to keep his work “pure devotion”amazon.com.

In Odisha, Sarala Mahabharata (c. 15th c.) by Sarala Das remains famous. Though its core is the Sanskrit Mahabharata, Sarala’s narrative is distinctly Odia: it adds local gods, folk stories, and philosophical debates. These works are celebrated in Odisha’s festivals and dance forms today.Collectively, these epics prove that Indian mythology is not monolithic. Each region wrote in its own language – Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Odia, Assamese, etc. – and produced masterpieces. Together they form a treasure map of forgotten lore.

Folk Tales and Puranic Lore

Beyond formal “epics,” many folk tales and Purana narratives enrich the tradition. For example, stories of regional deities like Nongpok Ningthou (Manipur) or Khandoba (Maharashtra) are told in poetic ballads. Puranic tales such as Devi Bhagavata (goddess-centric) or the Tamil Periya Puranam (lives of Shaivite saints) are epic in scope but often overlooked in popular retellings. Folk-lore like the Bhili Rasals or Santhali myths also preserve ancient motifs in tribal communities. Even these reveal the same themes of valor, sacrifice, and cosmic justice, under the wider umbrella of Indian mythology.

Key Takeaways:

- Epic Diversity: India’s “hidden” epics include Jain, Buddhist and bhakti works (e.g. Manimekalai , Basava Purana en.wikipedia.org) beyond just Hindu epics.

- Regional Voices: Each language gave its own epics – Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Assamese, Odia etc. – reflecting local culture and morals.

New Heroes: Heroes like Kannaki (a chaste wife who becomes goddess) and Basavanna (a reformer-saint) emerge, widening our hero roster beyond Ram/Krishna.

FAQs

Q: What are some lesser-known epics of Indian mythology?

A: Beyond the Ramayana/Mahabharata, India has many. For example, Silappatikaram and Manimekalai are Tamil epics about Kannaki and her daughter. Karnataka’s Adi Purana and Pampa Bharata (10th c.) by Pampa are early Kannada epics. Assam’s Bhagavat of Sankardev (15–16th c.) retells the Bhagavata Purana in Assamese. These are just a few among dozens of regional epics.

Q: Why are Tamil epics significant in Indian mythology?

A: Tamil epics like Silappatikaram (1st c. CE) and Manimekalai (5th–6th c. CE) introduce strong female characters (Kannaki and Manimekalai) and new philosophies (Buddhism/Jainism) into the mythic fold. They also integrate Vedic, folk and classical elements uniquely. In other words, they show how Indian mythology weaves together diverse faiths and cultures, which matters for understanding India’s spiritual heritage.

Q: Who are Kannaki and Basavanna in these epics?

A: Kannaki is the fiery heroine of Silappatikaram. A virtuous wife, she curses a king after injustice befalls her husband, illustrating the power of chastity and righteousness. Basavanna (Basaveshwara) is the philosopher-saint of the Lingayat tradition, hero of the Basava Purana. His epic life story preaches devotion to Shiva and social equality. Both figures, rooted in regional lore, enrich Indian mythology by embodying devotion and justice in local contexts.

Q: What role do regional languages play in Indian mythology?

A: Enormous. Sanskrit was once the lingua franca of epic tales, but as regional languages (Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, etc.) blossomed, poets translated and retold myths in local idioms. The result: Indian mythology branched into many traditions. Each language produced its own “great epics” – for example, Tamil’s Aimperumkappiyam, Kannada’s Purana classics, Telugu’s Puranas, Assamese Bhagavat, Odia Sarala Mahabharata, and more. These works ensure that mythic wisdom belongs to all communities, not just Sanskrit scholars.

Q: How can I learn more about these hidden Indian epics?

A: Many of these epics are available in translation today. To start, read introductions or stories about Silappatikaram, Manimekalai, or Basavanna’s life. You can also explore the Puranas (like Devi Purana or Skanda Purana) which preserve many regional tales. For deep dives, look for scholarly books on regional literature. On VedicWars.com, see our articles on related topics (e.g. “Kannagi’s Legend” or “Lingayat Reformers”) for summaries and context.

Conclusion

In exploring these hidden epics, we’ve discovered that Indian mythology is far richer than its two most famous stories. Each regional epic is a microcosm of culture — it teaches local values (honor, devotion, wisdom) while still asking the universal questions of fate and dharma. Together, they remind us that mythology is a living ocean, not just a single river. Even today, these stories inspire festivals, art and devotion (Kannaki is worshipped as Pattini Amman; Basavanna’s vachanas are sung in Karnataka). As modern readers, we gain insight into how diverse Indian spirituality truly is. The takeaway? Keep digging! There are still many sagas and heroes to uncover.